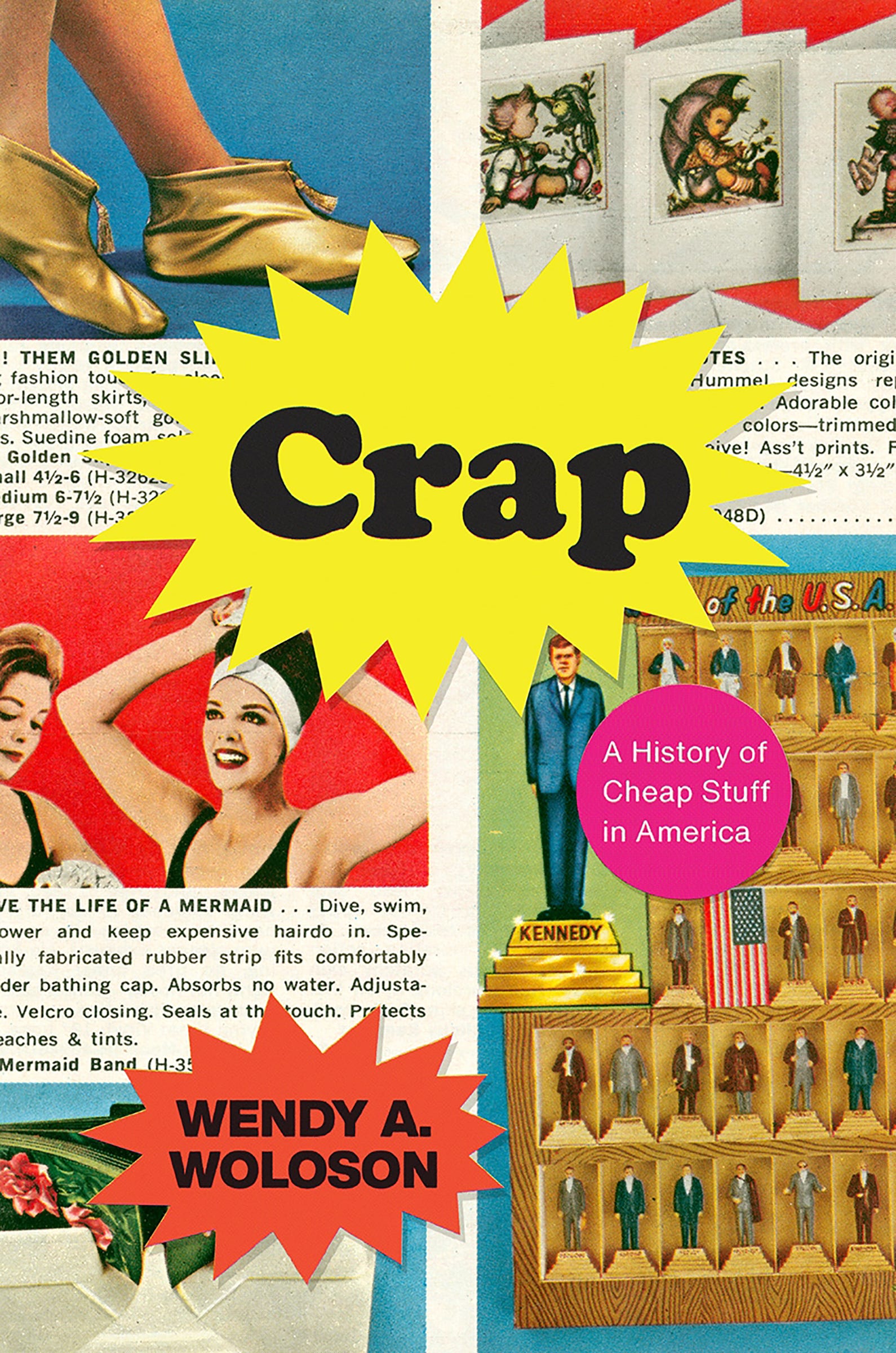

Crap: A History of Cheap Stuff in America by Wendy A. Woloson (University of Chicago Press)

Part history, part sociology, with some firecracker economic insights to boot, Crap: A History of Cheap Stuff in America arrives as a much-needed etymology for everyday goods that we take for granted. But as its title states, Crap isn’t a paean to the well-made, flawlessly designed goods that have become ubiquitous in American households. Instead, its author, Wendy A Woloson, charts the proliferation of cheap goods from the eighteenth century to the present day. Elucidating, witty, and compulsively readable, the case that Woloson builds suggests that, despite massive achievements in industrialization, the United States’ purview isn’t the cotton gin, or the Model T, or any of the all-time light bulbs hovering above inventors’ heads that populate the history books. Rather, it is the cheap tin flatware and hosiery found in the bins of five-and-dime stores, the free toys fished from the bottom of cereal boxes, and the snake oil solutions in search of a problem that, when viewed in aggregate, reveal themselves to be America’s true claim on innovation.

From this narrative, a compelling and dour critique emerges. Despite goods purchased on the cheap failing consumers in catastrophic ways, carrying no discernible value, or frequently wearing out and requiring continued replacement—thereby making the goods more expensive, in the long run, than buying something more expensive—American consumers continue to flock toward crap because of the sense of abundance it gives them in spite of a bleak economic picture. If this weren’t depressing enough, the onslaught of crap proves so evasive that, in many instances, consumers are unable to tell the difference between a well-made product and a crappy one. Patenting useless “innovations” on standard products to gain a marketing advantage, stocking items outside of packages in stores and individually pricing them to feign the appearance of value: one of the more pervasive themes that Woloson outlines is humanity’s capacity to take advantage—out of necessity or habit as a consumer, but also in a predatory manner as a business owner.

Consumerism critiques are a well-beaten horse; aside from its levity, Crap serves as a welcome addition to that canon by highlighting the numbness of purchases made when individuals have no connection to the goods’ source. The collateral damage of industrialization wisps through its pages, like celluloid flowers going up in smoke.