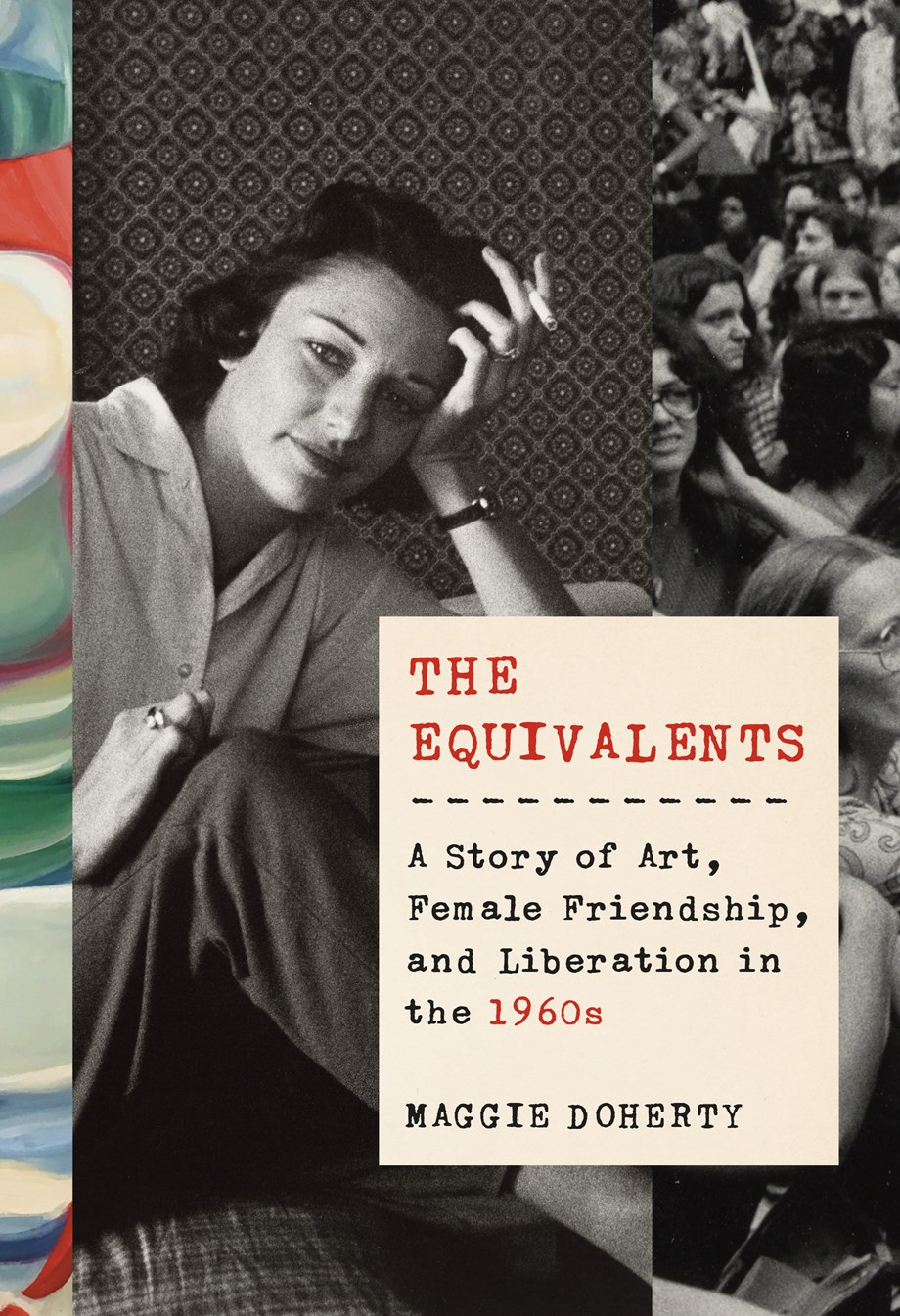

The Equivalents: A Story of Art, Female Friendship, and Liberation in the 1960s by Maggie Doherty (Knopf)

Maggie Doherty’s group biography The Equivalents offers a thoughtful look at the underexamined years before the second-wave feminist movement as well as the importance of a “room of one’s own.” Centered on the first years of the Bunting fellowship at the Radcliffe Institute, a first-of-its-kind opportunity for women founded in 1961, The Equivalents documents how, in Doherty’s words, “for the women it supported, the Institute was nothing short of life changing (one called it her ‘salvation’).”

Initiated by Radcliffe president Mary Ingraham Bunting, the program was specifically designed to enable accomplished women – women who had written books, completed doctorates, etc. — to create space for their work against the pressures of motherhood and mid-century cultural norms. The fellowship application’s requirements stated that the program was open to women with a doctorate or “the equivalent,” the latter enabling the participation of poets Anne Sexton and Maxine Kumin, the journalist Tillie Olsen, the painter Barbara Swan, and the sculptor Marianna Pineda in the first few fellowship classes.

With this group of five — the doctorate-less “equivalents” — as her focus, Doherty explores how the Bunting fellowship encouraged women to grow as writers and artists. Importantly, the fellowship provided these women with the funding to enable such growth. Associate scholars, according to Doherty, received a $3,000 stipend, about $25,000 today. For some, like Kumin, this money meant hiring babysitters. For others, like Sexton, a member of the fellowship’s first class, it meant quite literally building a room of her own: a porch was converted into her home office. (Sexton, to Bunting’s chagrin, also used the money to build a pool.) For the working-class writer Olsen, it meant having the funds to move across the country, from San Francisco to Cambridge, and the time to finally tackle a book-length project. Just as significant as the money, though, was the like-minded community the fellowship provided these women, according to Doherty. Fellows stayed in touch and pursued their work with the same seriousness even in the years after their time at the Radcliffe Institute.

Group biographies, especially of women, have become increasingly popular in recent years. Doherty’s serves as a model for how a book primarily based on the private interactions between women can speak to larger histories and illuminate the obscure corners of American cultural history. “The sad irony of the Equivalents is that the movement they helped give birth to was not one in which they could participate fully,” Doherty writes toward the end of her book. “The Institute was the harbinger of a much more radical reordering of American society…. The Equivalents were women born too early; by the time the women’s movement gained full steam, each of them was well established in her life and ways.”