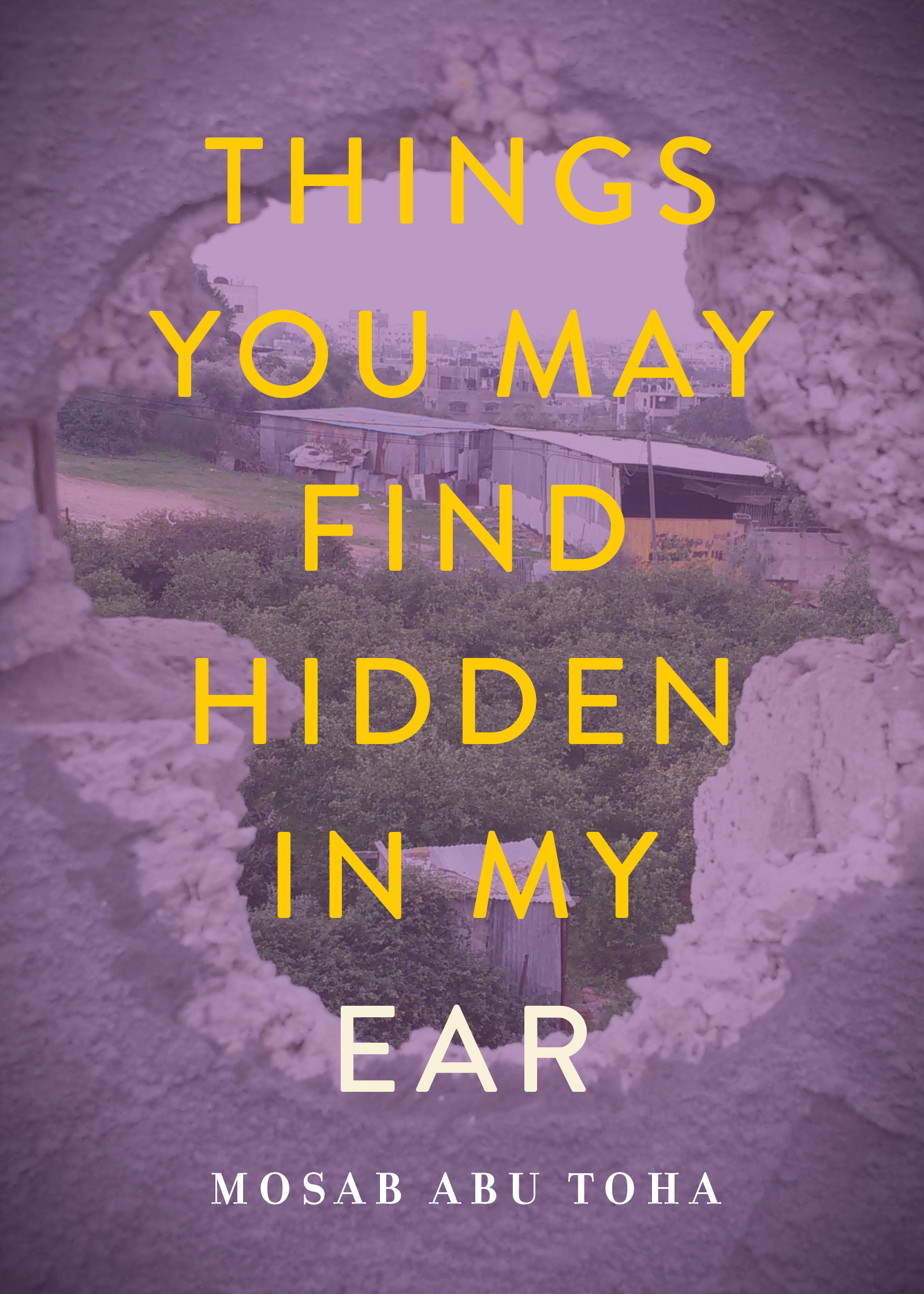

The Gaza of Mosab Abu Toha’s childhood is a land of tortured ambiguities, a precarious, uncertain place where “you don’t know what you’re guilty of,” where “breathing is a task” and “smiling is performing / plastic surgery,” as he writes in two poems from Things You May Find Hidden in My Ear (City Lights). Yet Palestine is also a land of poetry, of Mahmoud Darwish and Tawfiq Ziad. Abu Toha has now slipped seamlessly into that mantle, and this first collection announces his arrival at the helm of a new generation of Palestinian poets.

The running theme through Abu Toha’s poetry is the menace of unpredictable violence. In Gaza, “streets are nameless” and “if a Palestinian gets killed by a sniper or a drone / we name the street after them.” He writes that he weaves his poems with his veins: “I want to build a poem like a solid home,” he elaborates, “but hopefully not with my bones.” In contrast stands Abu Toha’s take on the risks endured by the people of Israel: “Their ears hurt when they hear sirens, / but we are made deaf by explosions. / / Their muscles stiffen with fear on their way to the shelters, while ours are pierced by boiling shrapnel.”

What makes Abu Toha’s work resonate so strongly is his gift for the particular. By avoiding panoramic generalizations, he hones in upon evocative images that capture the larger plight of his people: an uncle’s prayer rug, “where dozens of ants slept on wintry / nights, before it was looted and put in a museum,” a girl who “sinks / her small hands into the pockets of her jeans, / moves them / as if she’s counting / some coins” after losing seven fingers to the war. Often the violence is portrayed obliquely, adding to its power, such as his description of the aftermath of a missile strike: “Angels get hold of my infant niece. / We look around and find only / her milk bottle.” And Abu Toha has a gift for capturing unexpected details that speak to larger human suffering: “In Gaza, when the electricity / is cut off, we turn on the lights, even in broad daylight. That way, / we know when the power’s back.”

Although deeply grounded in the Palestinian experience, Things You May Find Hidden in My Ear speaks a language of universal anguish. The lines,

They once said Palestine will be free tomorrow. When is tomorrow?

What is freedom? How long does it last?

echo those in the Jewish Passover service, “Next Year in Jerusalem.” Like the Israel of my own grandparents, Abu Toha’s Palestine is for now, he writes, “a country that exists only in my mind.” He reminds readers that, “Borders are those invented lines drawn with ash on maps and sewn / into the ground by bullets.”

Yet a photo spread at the center of the volume includes the caption, “Through it all, the strawberries have never stopped growing,” below a picture of these luscious fruit. A stoic message, but also a testament to hope.