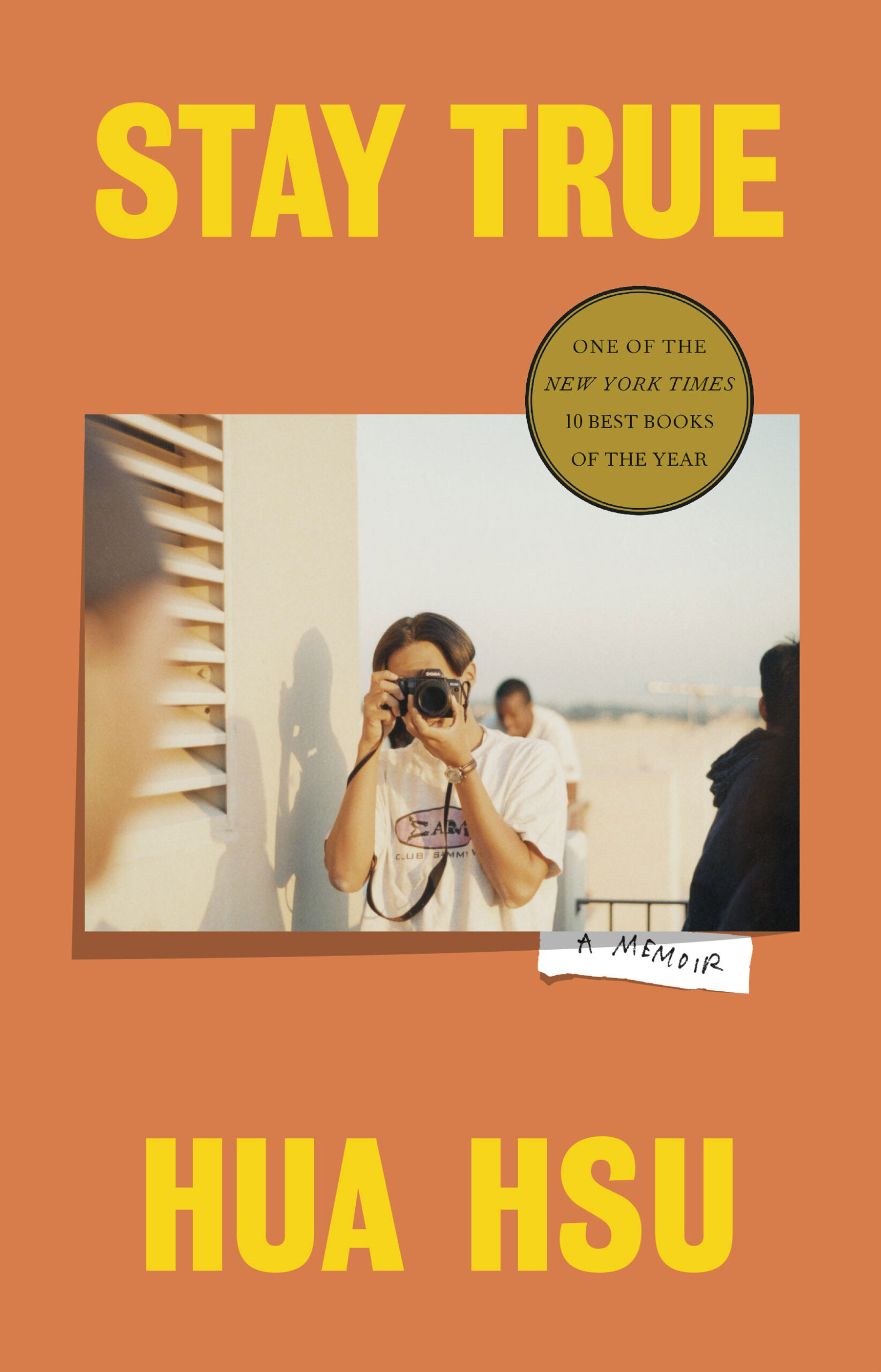

“History is a tale we tell, not a perfect account of reality,” reflects a young Hua Hsu to his friend Ken in Stay True (Doubleday). “You just have to figure out whether you trust the storyteller.” This is certainly the case in Hsu’s own book, where he earns the trust of readers by revealing the unexpectedly tender intimacies of male friendship in a vulnerable coming-of-age memoir that explores grief, movies, music, language, and the complicated catch-all term Asian American.

Mainly set on Berkley’s campus in the late 1990s, and expansive in its examination of the political and counter-culture arts scene of that time and place, the heart of Hsu’s memoir is his friendship with Ken, a fellow Asian American undergraduate that Hsu slowly warms to over the course of their freshman year. The friendship begins in dissonance: Hsu is a second generation Taiwanese American, while Ken’s Japanese American family has made their home in the U.S. for decades; Hsu reveres all things alternative, while Ken blithely dons the mainstream tastes of the fraternity he pledges. The two eventually discover what they share both culturally and philosophically, only to have their unlikely friendship cut short when Ken is murdered in a carjacking.

Hsu writes in the acknowledgements that “this is a book about being a good friend,” and it is, his meditation on the topic gaining power from its devoted particularity. Because the book is also a love letter to the act of writing and the desperate need to record everything and anything, as if each scrap of memory might hold equal value, the reader encounters meticulously assembled zines, earnest journal entries, and phrases scribbled on the backs of peeled beer bottle labels. But the book itself is not a collage. Hsu’s insights into his process as a writer allow the memoir to interrogate its act of literary time travel, with Hsu pursuing his goal with the fervor of a clear-eyed historian in the archives of the heart.

The best memoirs aren’t defined by a singular tragedy, and though Stay True is ostensibly built around Ken’s death, his loss is not the book’s story. Hsu returns repeatedly to Derrida’s theory on friendship as the act of knowing another, and in his book he does the careful, compromising work of knowing—a place, a time, and a person who can never be separated from those elements. In doing so, he’s crafted a transformative addition to the Asian American canon and to the critical conception of what a memoir is capable of. In addressing his desire as an undergraduate to dig into the acts of solidarity and action among the Asian American generations that preceded his own, Hsu writes, “I wanted to learn only about histories that had been denied to us.” And for Ken and those who loved him, the futures that were denied, too. For all the deep labor of reflection in Hsu’s book, his memoir is about the harder work of moving forward, missing pieces in hand.