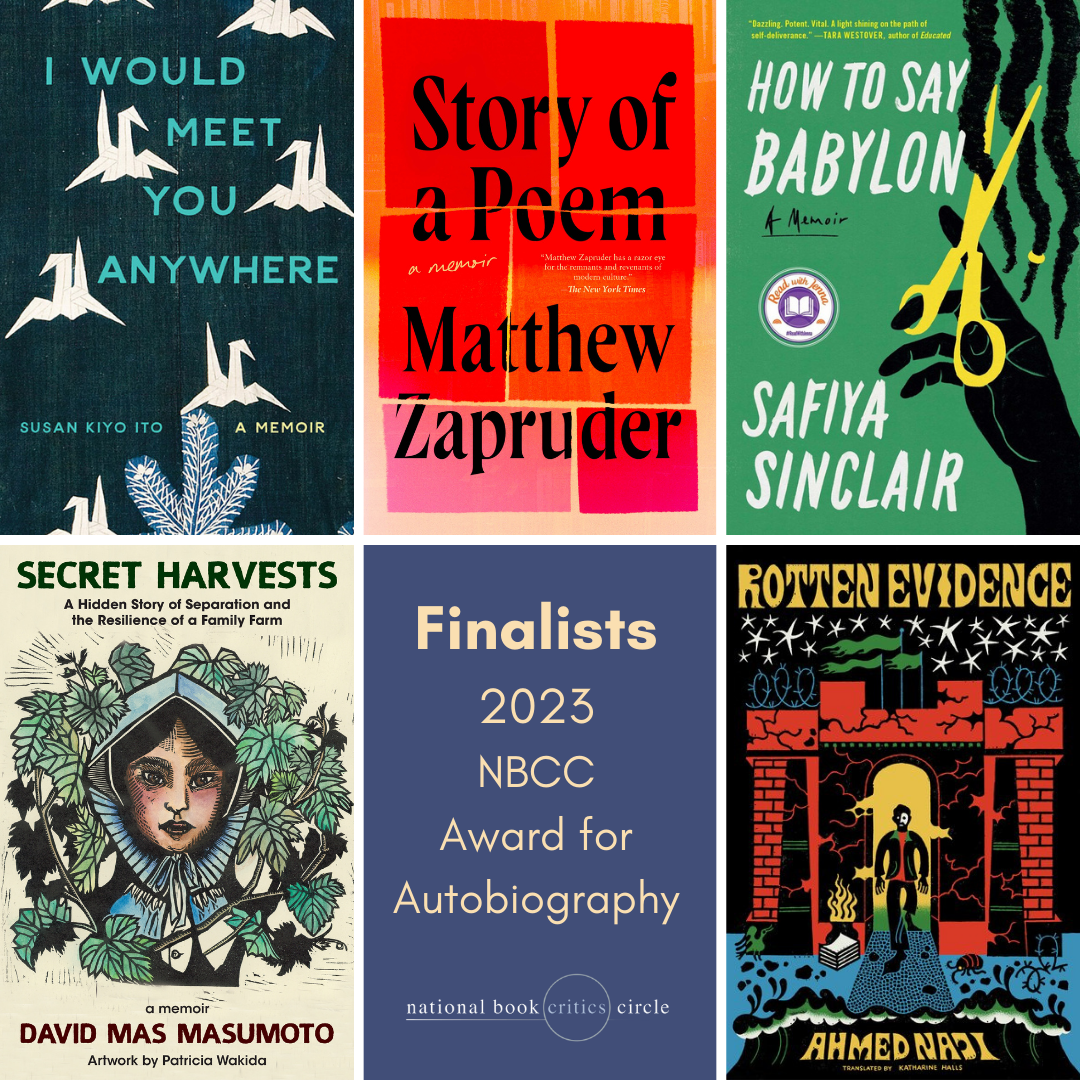

Each year, our board members write citations of the finalists for the National Book Critics Circle Awards in a feature we call 30 Books in 30 Days. We’re honored to continue this year’s edition with brief reflections on the finalists in our autobiography category.

Susan Ito, I Would Meet You Anywhere: A Memoir (Mad Creek Books, an imprint of The Ohio State University Press)

Susan Ito’s heart-rending and courageous memoir holds a secret at its core. At nineteen, as a transracial adoptee raised by nisei parents, she sleuths out the identity of her Japanese-American birth mother, defying laws that keep adoption records sealed. Their fraught first meeting is the beginning of decades of emotional ebbs and flows, as Ito’s biological mother cuts off contact with her repeatedly to maintain anonymity and avoid naming the man who fathered her. What sustains Ito: Marriage, motherhood, advocating for adoptees, and writing her own story. I Would Meet You Anywhere illuminates the complexities of identity, family, and belonging.

David Masumoto, with artwork by Patricia Wakida, Secret Harvest: A Hidden Story of Separation and the Resilience of a Family Farm (Red Hen Press)

Secret Harvests limns the compounded tragedy of the Japanese internment for one family, when a cognitively disabled member, herself disabled via the racism of inadequate medical care–was separated and “lost” to the family during World War II. David Mas Masumoto uncovers the smallest thread of the story and achieves the seemingly impossible feat of reconnecting the lost family member whose story had been lost to racism but also family shame. In stark, stunning prose combined with Patricia Wakida’s evocative woodcut prints, Secret Harvests manages to take absence and turn it into presence, illuminating the hard-won resilience and joys as well as the darker corners of the author’s family history—and that of our nation as well.

Ahmed Naji, translated by Katharine Halls, Rotten Evidence: Reading and Writing in an Egyptian Prison (McSweeney’s)

Ahmed Naji’s eloquent, and at times searingly funny, memoir of his time spent in an Egyptian prison, Rotten Evidence, reveals the importance of literature as a form of self-liberation. Naji was convicted of “violating public modesty” after an excerpt from his novel Using Life was published in a journal in Egypt. Naji recounts his experiences in detail, from the mundane daily indignities of incarceration to the camaraderie that develops between prisoners. The memoir is also an erudite literary text as Naji expounds on works of Egyptian literature, the Arabic language itself, and the limits imposed by successions of authoritarian governments. Katharine Halls’s lively translation captures Naji’s distinctive voice, by turns intellectual, enraged, sardonic; Naji comes across as someone who remarkably can always crack wise about his bully jailers and the ignorance of his government’s censors.

Safiya Sinclair, How to Say Babylon: A Jamaican Memoir (Simon & Schuster)

How to Say Babylon, Safiya Sinclair’s lyric memoir, is intimate, unforgettable and a shining example of why poets should write prose. The Eden of Sinclair’s Jamaican childhood is irrevocably altered under her father’s strict Rastafarian upbringing which first constrains, and then threatens, her life. Her poetic soul is matched by her resilience and perseverance and is the foundation of her courageous expressions of individuality and agency. Sinclair expertly weaves moments both harrowing and idyllic in a way that is candid, yet still generous to even those who have harmed her, which speaks both of her sensitivity and strength, and makes this memoir singular, universal and transporting.

Matthew Zapruder, Story of a Poem: A Memoir (Unnamed Press)

Matthew Zapruder’s Story of a Poem pursues two questions simultaneously: what makes a poem work, and what makes a life matter. If those questions seem to belong to different realms of meaning, it is the quiet brilliance of this book to convince you of their interdependence. The story is of the creation and revision of several poems—messy, developing drafts included—and the equally messy process of understanding a child whose autism diagnosis wrenches the author’s first draft of parenthood into a new shape—all while the air outside darkens with wildfire smoke. It is rare to see the competing calls to creativity and care explored so literally, and with such urgency and tenderness, as they are here.