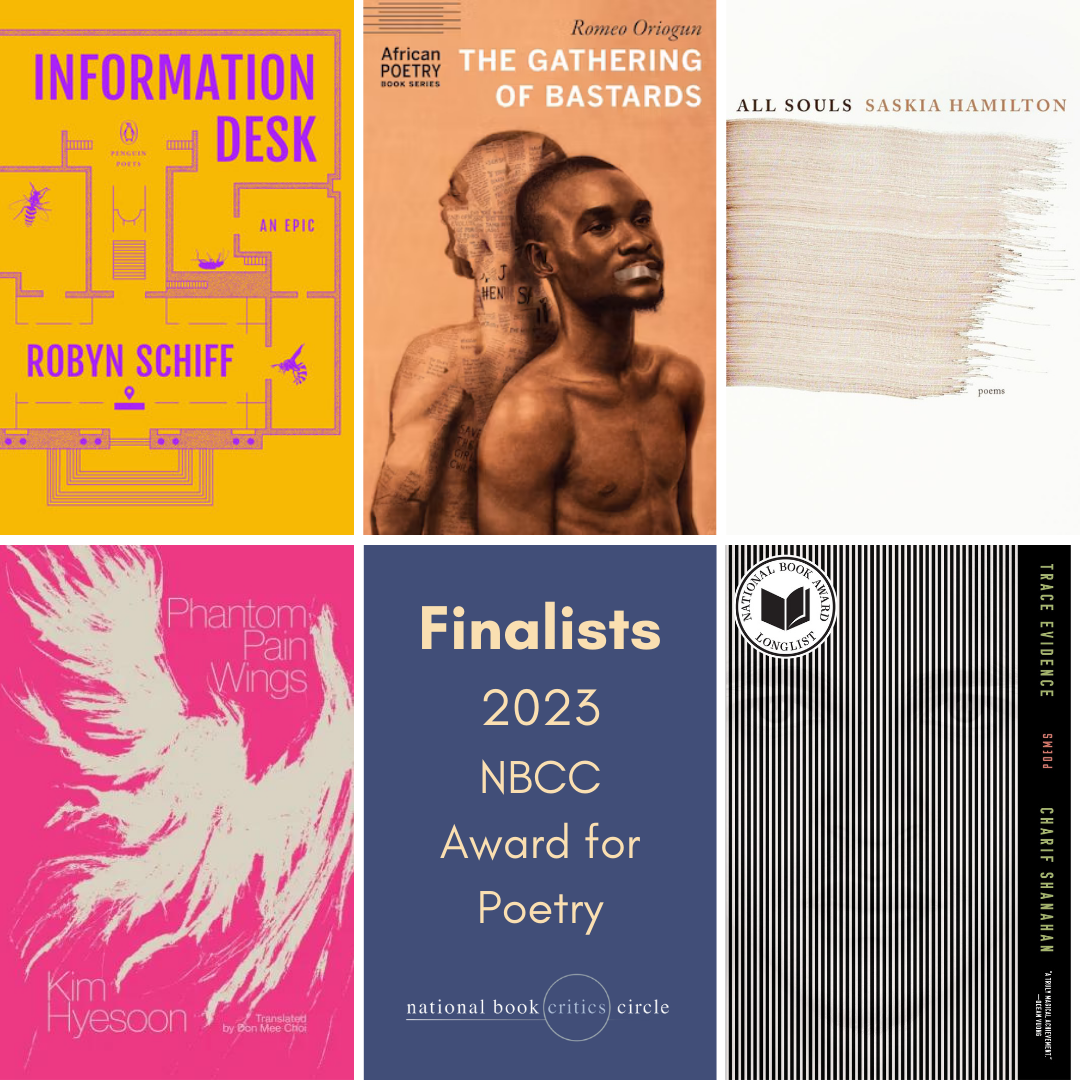

Each year, our board members write citations of the finalists for the National Book Critics Circle Awards in a feature we call 30 Books in 30 Days. We’re honored to continue this year’s edition with brief reflections on the finalists in our poetry category.

Saskia Hamilton, All Souls (Graywolf Press)

In the exquisite and profoundly affecting All Souls, completed just before her death, Saskia Hamilton wonders if writing can be “a form of practice or of preparation for death” and answers with a meditation on all the things that mattered deeply to her: family, memory, art, and literature. What she creates is something surpassingly rare, a kind of auto-elegy that is all the more moving for being devoid of sentimentality and self-pity, a vision of a brilliant mind mulling over the shards of what she knows, trying to see into and past death, not to vanquish it but to capture life, “caught in the far gone far alone glance / of mortality.”

Kim Hyesoon, translated by Don Mee Choi, Phantom Pain Wings (New Directions)

With stunning originality and audacity, Kim Hyesoon creates an alternative imaginative universe that reflects a consciousness battered by and overcoming life’s agonies: the aftereffects of war and dictatorship, the oppressions of a patriarchal society, the death of a father. In Don Mee Choi’s powerful translation of Phantom Pain Wings, the presence of the multi-faceted creature called “bird”—nemesis, inner daemon, doppelganger, muse—reverberates outward until, as with all great poetry, it assumes the fragile, mortal proportions of art itself: “I thought about bird flying freely in the ruins / bird that will fall if I don’t keep writing.”

Romeo Oriogun, The Gathering of Bastards (University of Nebraska Press)

“Perhaps exile is us running through history // I have not to give, even my body is empty of a country.” So begins Romeo Oriogun’s breathtaking The Gathering of Bastards, a multitemporal saga of migration charted against journeys of queerness and subsequent exile. Nigerian-born Oriogun’s poems are rooted between boundaries, engaging with war and dictatorship while employing a lyricism that instills a sense of magical possibility. Despite repeated losses, Oriogun pens an expansive dream of freedom: “Having known that there is no home apart from terror, / I lend my voice to our survival. I demand a wild life.” Through the wild lives of these poems, Oriogun offers readers a profound communion.

Robyn Schiff, Information Desk (Penguin Books)

With a sweep that encompasses the intelligence, eroticism, and callousness of the Western art canon, Robyn Schiff’s Information Desk presents a mundane setting for the epic: the eponymous desk at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, where the poet worked in her youth. Yet for all its cataloguing of the indignities of the role, Schiff’s epic poem refuses to stay grounded, taking readers on a whorl through art history, her personal relationships, and the behavior of parasitic wasps. What unites these topics is the symbiotic relationship the subjects have with their muses

(or hosts). Like the book itself, these relationships are sometimes beautiful, oftentimes brutal, and alluring in their observation that not all monuments are erected on equal footing.

Charif Shanahan, Trace Evidence (Tin House)

“Dear one: I was trying to enter my own life, I felt outside my own life. I was / Looking, trying to find a door.” In the searching intimacies of Trace Evidence, Charif Shanahan uncovers his own hard-earned definitions of identity amidst the dislocations of a life at the margins–postcolonial, queer, biracial–in order to inhabit life on his own terms. A near-fatal accident in Morocco, the home country of his mother, becomes the focal point for gorgeously frank and delicate lyrics that both query and implore: “Is it possible my function is to hold / All the intricate, interstitial pain / And articulate clarity? / Tie a boat to my wrist, I sprout wings.”