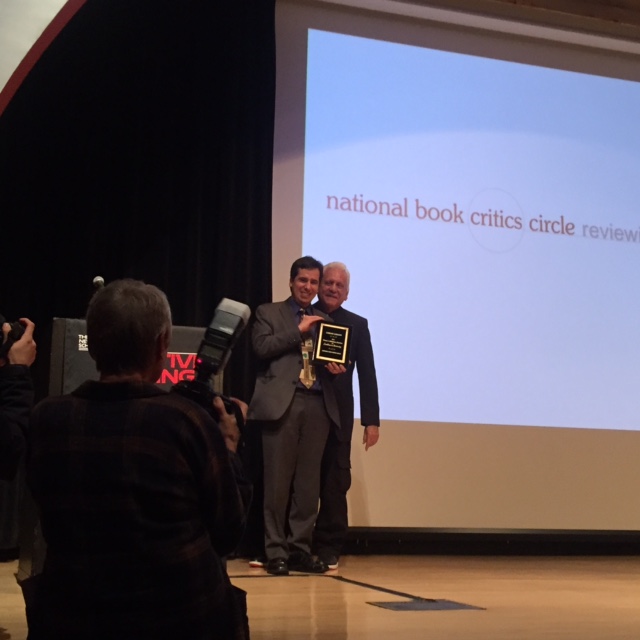

Good evening, and thank you for that generous introduction. I’d like to thank the National Book Critics Circle for seeing fit to hand its reviewing award this year to a rookie book critic, which means that right now my elation is lathered in insecurity.

I’m supposed to say something about my approach to criticism. To be honest, I’m still trying to figure it out. I’d been at The Washington Post for about ten years – overseeing coverage of economics, national security, and our Sunday opinion section Outlook – when I learned that Jonathan Yardley was going to retire, and I thought, “now that could be an interesting job for me.” So it was opportunism more than anything else.

But when you’re looking to succeed someone who has been in a job for more than thirty years, and to much acclaim, you need to say how you’re going to do it your own way. So my pitch was to try to bring book criticism to the center of the mission of The Washington Post – because nonfiction books are not just great literature, or big ideas, or feats of writing and reporting. They are, overwhelmingly, news.

Sometimes it’s easy to see them that way. Last summer, I wrote about the memoirs of Donald J. Trump, in which he writes, quite forthrightly, about his capacity for deception, or what he calls “truthful hyperbole.” And last month, I wrote about Hillary Clinton’s “It Takes a Village,” which, twenty years after its publication, is still the best distillation of her political project.

But those are obvious – they’re politicians or public figures, so it’s easy to regard their books as news. With other works, it gets murkier. If I read Susan Southard’s “Nagasaki,” is it fair to the book, to the author, to the survivors she writes about, if I review it in the context of the Iran nuclear deal? If Monica Lewinsky happens to give a TED talk about the shaming she endured during the 1990s on the same week that I happen to be reading Jon Ronson’s “So You’ve Been Publicly Shamed,” should that coincidence color the way I review the book? Should I let it? And if Renaissance historian Victoria Coates writes a book about the interplay of art and democracy over the centuries, should the fact that she is Ted Cruz’s top foreign policy adviser affect how I see the book or the insights I hope to tease out?

The answer for me, in all those cases, is YES! Absolutely, yes. I do feel a little guilty about it, though. After all, when I’m reviewing a book that may have been years in the making, why should I be distracted by whatever is in the news that particular week, or by whatever I see on my Twitter timeline?

But I am distracted by all that, or, as I’d rather put it, informed by all that. Rather than read a book as an entirely self-contained work, or assess it against some literary standard or canon, I’d rather measure it against the moment. And depending on the moment, books can make news again and again. Bill Cosby’s bestsellers from the 1980s, considered so funny and cute and adorable back then, are revealing today in an entirely unexpected way, a creepy way – a newsworthy way. And reading Alexis de Tocqueville’s “Democracy in America,” like I did last December, is an entirely different experience given the state of American politics today, and different for me, in my first months as an American citizen. It is, in essence, a new book.

To say that books are news does not demean them; it exalts them. It acknowledges that in whatever age they’re read, books will always be in dialogue with the times. This just happens to be our time.

Thank you for this award. It’s an enormous honor.