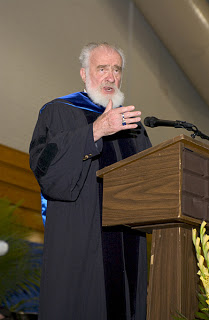

Today's posts will focus on W.D. Snodgrass's “Not for Specialists: New and Selected Poems,” a finalist for the 2006 National Book Critics Circle Prize in poetry.

Today's posts will focus on W.D. Snodgrass's “Not for Specialists: New and Selected Poems,” a finalist for the 2006 National Book Critics Circle Prize in poetry.

Look around for information on W.D. Snodgrass and you will find it impossible to escape biographical characterizations of him as a “confessional” poet; he is often spoken of as the originator of the practice of the personal, as if Whitman had no such proclivities as toilsome he wander'd Virginia’s woods. It is a contention that holds only to the extent that Snodgrass' early work — notably from Heart's Needle, which won the Pulitzer Prize in poetry in 1960 — stood in stark contrast to the influence and tradition extending from the likes of Pound and Eliot to expunge personal experience from the poem as if it were kryptonite. Snodgrass himself mentions X.J. Kennedy's fear, expressed in reviewing Heart's Needle, that “open-faced heart sandwiches” would become the order of the day in poetry (see the Kenyon Review)

Luckily for us all, poems from Heart's Needle are included in Not for Specialists: New and Selected Poems, partly a retrospective of a half-century of Snodgrass's work and a finalist for the NBCC poetry award this year. Looking back, we suspect that it was Snodgrass’s blunt, non-elliptical approach and the prospect that poet and poetic persona might be one and the same, that might have seemed so startling in its time. These poems still startle, not because they represent a stylistic departure today but because Snodgrass's often sober, not to say somber, writing employs a directness that shows sentiment and the sentimental to be categorically different things. “Come, let us wipe our glasses on our shirts:/Snodgrass is walking through the universe,” he declares in his opening poem, “These Trees Stand …,” perhaps a statement of poetic mission. Reading his new poems in the collection, one is surprised to find strong consonance with his earlier work — frequently formal (rhymed, for example), the newer poems swing back toward elements that echo their forebears. (His sets of “The Fuehrer Bunker” poems, also represented in Not for Specialists, are radical departures in form and tone; more below.)

With poems weighted toward the naturalistic and often drawing from nature subjects as well, the mortality of all things and the fight against entropy, whether in relationships or the body, is a consistent concern in Snodgrass's work. “Some things that you still loved might still endure,” as he puts it in “Mutability.” And his wiped-clear glasses in a poem that chronicles the seven-month death fight of Old Fritz, “A Flat One,” observes the medical machinery “On which we had tormented you/To life,” and comments,

Even then you wouldn't quit.

Old soldier, yet you must have known

Inside the animal had grown

Sick of the world, made up its mind

To stop. Your mind ground on its separate

Way, merciless and blind,

This is a typical Snodgrassian insight, quite stark and alloyed with only a trace of sweetness (the tenderness of “Old soldier”). Snodgrass does not lack for sweetness — in one of his newest poems, “Farm Kids,” he lauds his neighbors, whose “less keen hungers and kinder drives/make sure they'll make nothing of their lives but lives” — but he sees the world as mitigating it. Here is a look at the human condition through the found body of a rodent, “The Mouse”:

We live with some things, after all,

Bitterer than dying, cold as hate;

The old insatiable loves,

That vague desire that keeps watch overhead,

Polite, wakeful as a cat,

To tease us with our lives

The “Feuhrer Bunker” poems (which date from the late 1970s and mid-1990s), in which Hitler, Goering, Goebbels, Himmler, Eva Braun and others are personified, are the riskiest of Snodgrass's poems, the most inventive in form, and are tonally diverse, even including whimsy. (They raised some critical hackles, but Mel Brooks's “The Producers” preceded them in this sense, 1968.) Himmler's read like telegrams sent on graph paper, in which he insists “my stars still say I must succeed.” Eva Braun, given to singing American songs, has couplets from “Tea for Two” interpolated in her poetic stream of consciousness. Hitler's personal secretary Martin Bormann addresses his wife as “Dearest Beloved Momsy Girl.” Albert Speer asks, “Lord, Lord, who ever said that you can’t build on lies?”

Snodgrass’s poetic eye says so, for one. In the “Night Voices” section of his “Nocturnes,” one of his new poems, a discarded watch buried in a drawer of outworn underwear chirps in the night like

these memories

of some that you once loved who'd never care

to hear from you, of questions you’d scarce dare

hear. of what fear

underlay those days you used all wrong

or didn't use. Just how long

can shrieks growing so weak

still carry on? We'll learn, no doubt,

which of us can last this out.

Snodgrass has.

—Art Winslow, NBCC board member