This essay first appeared on Critical Mass three years ago, in November, 2007, the week after the Mercantile Library Center for Fiction in New York (now the Center for Fiction) sponsored a gala awards ceremony for three prizes: the John Sargent, Sr. Award for First Novel; the Clifton Fadiman Medal, for a work of fiction by an American author which deserves rediscovery and wider readership; and the Maxwell E. Perkins Award “to honor the work of an editor, publisher, or agent who over the course of his or her career has discovered, nurtured and championed writers of fiction in the United States.”

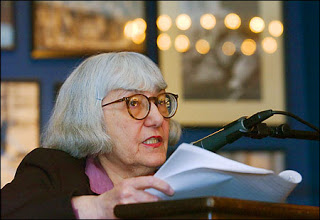

The Sargent Award went to Junot Diaz for The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao (the novel also won the NBCC award in fiction that year), the Perkins Award to Drenka Willens, long-time editor at Harcourt, and the Fadiman Medal to Lore Segal for “Other People's Houses,” (Segal recently returned to the Center for Fiction to appear on an NBCC Reads panel on “conjugal lit.”) Her novel Other People's Houses was introduced by four-time NBCC finalist (and winner) Cynthia Ozick. She has kindly allowed us to post her introductory remarks here.

SOMETIME IN THE EARLY sixties of what we must now call the last century, the New Yorker published a series of autobiographical stories by a writer whose voice was unlike any other I had ever known. The subject was extreme, yet there was no bitterness in it, and no equanimity either; no turbulence, though the effect was to leave the reader in turmoil; and the scrupulously introspective tone, without a scintilla of self-pity, truthful almost to the point of matter-of-factness, could nevertheless bring on a wash of pity deeper than tears. But it was the kind of pity that is kin to wisdom and ignites new understanding. There was an acute physical awareness in that voice too: a painterly evocation of rooms and wallpapers, colors and furnishings, some beautiful and tasteful, others ignorant and shabby; and gardens and landscapes and clothing and bodies and faces. As each new section of the series arrived, I became mad with impatience for the next. And when at last Lore Segal’s Other People’s Houses was brought out in its final form as a novel, I took my timid heart in my hands and made the rounds of editorial offices to plead to be allowed to review it, though I had never before written or published a review.

That forty-year-old review made its way, somewhat mysteriously, into the newest reissue of Other People’s Houses, where it appears as a Foreword. I turn to it now in bewilderment. “Dry, cold, literal, even numb” is how I described Other People’s Houses in 1965, even as I wrote of it admiringly; and it was for its being dry, cold, literal, and numb that I praised it. I meant, of course, that its dramatic theme — a lone refugee child taken in by an assortment of charitable strangers — might by a lesser pen have been made melodramatic and maudlin. I had been thinking, back in 1965, of the twentieth century’s cataclysms, and in particular of the German abductions of whole populations, and of the atrocities and genocide that followed. “In the end, then,” I wrote, “Lore Segal’s reminiscences are not so much about her life as about her time — our time.” This remains true, and I have not stopped thinking of these things, nor will they ever ebb or fade for my generation.

But when I found myself rereading Other People’s Houses last weekend in a frenzy of fresh marveling, I saw and felt something very different. Dry and cold? Instead, warmth and quickness. Numb? The very opposite, a consciously eager penetration into other people’s minds and feelings and perceptions, the interiors of their skulls even more than their sculleries and parlors. Along with the very intelligent child’s clear-eyed self-interrogation comes a flow of observation, judgment, subtle psychological acuity. To say it otherwise: the child at ten, vulnerable and dependent and effectively parentless, the object of the charitableness of a foreign people, was already an artist. She was, even then, one of those (in Henry James’s phrase) upon whom nothing is lost.

Other People’s Houses has not altered since my first reading, when, enthralled and appalled, I came to this extraordinary book in what I now take to be a half-understanding. I understood its significance as a historic social document; I understood its humane force; I understood it as a reflection of a period of barbarism contradicted, here and there, by a rare compassion; I understood its revelations of the unsuspected byways of guilt and hurt and humiliation and shame. What I believe I did not sufficiently see in my earliest reading was the imaginatively transcendent and humanly mundane power of its expression as a novel — as a novel of manners, a novel of class, a novel of character: and if this suggests a comparison to Jane Austen and George Eliot and the double-seeing Conrad of “The Secret Sharer,” that is no accident. And it is probably no accident also that it is the English, not the American, novel which comes to mind. You will not encounter Huck or Gatsby or Herzog in Other People’s Houses, but you will find Franzi, a brave and inspiring character as remarkable and indelible and brilliantly unforgettable as Dorothea Brooks. She is the writer’s mother, incontrovertibly; but she is also the artist’s ingenious muse. It may be because of the tirelessly courageous and everlasting figure of Franzi that Other People’s Houses will continue to be read two hundred years hence, when Hitler’s Europe will seem as remote to those unimaginable generations of the future as the Spanish Inquisition is for us. History, however horrendous, finally pales. Art, while it is never a palliative — art persists.

AND having come to the point — Lore Segal’s art — here I should stop. But let us permit the novel to speak for itself. In their native Vienna, Lore’s parents — Mr. and Mrs. Groszmann, he an officer of a bank, she an accomplished pianist — lived the sort of comfortable, optimistic, kindly life typical of middle-class, mostly assimilated Jews. Rescued from certain annihilation by Britain, they were grateful to be employed as a “married couple,” Mrs. Groszmann as cook and Mr. Groszmann as gardener. Here is a brief passage:

One day Mrs. Willoughby told my mother she thought it would be nice for her to meet some English people. My mother was surprised and gratified. Mrs. Willoughby said she had invited the vicar’s cook to take her tea with my mother and father on their next Sunday off.

It was a very wet afternoon. Mrs. MacGuire arrived at the back door on the dot of four. She was a stout, decent-looking middle-aged woman, dressed all in black. She let my father take her coat and galoshes but kept her hat on while my mother gave her tea at the kitchen table. She spoke with a heavy Irish brogue; my parents recognized only an occasional word of her conversation. My mother had baked a Viennese cake for her, which she understood Mrs. MacGuire to say was far too rich. Mrs. MacGuire asked for a piece of paper and a pencil, so that she might write down for my mother how to make a good plain sponge. At five o’clock, Mrs. MacGuire put on her coat and galoshes and went home.

After that, my parents always went out of the house on their free afternoons.

On a morning late in May, my mother fell down the stairs. She was overworked and sleeping badly, and she came through the curtain onto the landing at the head of the back stairs and went headlong with a tremendous clatter. Mr. Willoughby came rushing from the front of the house to the second-floor landing and ran down after her, but by that time my mother had picked herself up and was sitting on a step resting her head in her arms. She heard Mr. Willoughby’s trembling voice say, “What happened?” My mother raised her head. Mr. Willoughby, in his pajamas, had turned his avenging eyes up to where my father stood, petrified, at the head of the stairs, looking down. “Tell me the truth!” cried Mr. Willoughby. “Was it a fight?”

My mother explained that the fall had been an accident. She has told me how, through the dizziness and nausea, she wanted to stop talking, as if it was too much trouble — as if it were too late — to explain anything.

And so the Willoughbys had put my parents in their place; the refugees belonged to the class of people who eat in the kitchen, sleep on cheap mattresses, and throw their wives down the stairs in an argument — which goes to show that people have, after all, an innate sense of justice and cannot with equanimity be served by their fellows when these too closely resemble themselves.

My parents were meanwhile adjusting their image of their masters. “She has no sense of humor,” said my mother. “She doesn’t know any geography,” said my father, “and the naive questions that he asks me about the Nazis!” “They don’t know how to eat,” said my mother. “Do you remember the time I made them an Apfelstrudel and they asked for custard to be put over it?” “They don’t understand,” said my parents, and so they put the English in their place.

But my mother had a difficulty; she liked Mrs. Willoughby. She liked to see her on her way into the garden, wearing her blue-green kerchief that made her eyes more astonishingly blue, and there was about this thin, trim lady a quiet toughness, a presence, a capability in the firm, easy way she handled the reins of her household that was new to my mother and that she admired.

Even Mrs. Willoughby’s obtuseness was incorruptible. She came into the kitchen on a Sunday when it was raining too hard for my parents to leave the house and said, “Oh, Mrs. Groszmann! Since you are here, maybe you wouldn’t mind bringing in our tea?”

My mother minded it very much. She acquiesced in silent outrage. At the door, Mrs. Willoughby turned back. “But first why don’t you come up and get the linens to make up your little girl’s bed,” she said. “It’s this Thursday she’s coming, isn’t it?”

My mother followed Mrs. Willoughby to the linen closet, vowing never to think an ungrateful thought about any English person again. “Not these,” said the lady, laying some folded sheets in my mother’s arms. “These are our good sheets, and you don’t want to get her used to this kind of thing. Set them down on the tallboy.”

With my mother’s help, Mrs. Willoughby emptied the linen closet until she came to a pile of rust-stained sheets in the back. “There,” Mrs. Willoughby said, “and you and Groszmann had better take the morning off, too, and go up to London to fetch the little girl.”

“How good you are,” said my mother, close to tears.

“Then do you think you could catch the 5:15 down from Waterloo and be back in time to get our dinner? Maybe cold meat and a nice green salad and a tomato aspic that you could prepare in the morning, before you leave?”

Cynthia Ozick is the author of more than a dozen award-winning works of fiction and nonfiction. Her essay collection Quarrel & Quandary won the National Book Critics Circle Award, and her collection Fame & Folly was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize. Her novel, Heir to the Glimmering World, was a New York Times notable book and a Book Sense pick and was chosen by NBC's Today Book Club. Ozick's new novel, Foreign Bodies, is due out November 1, 2010.