It was raining most of the way as I drove from Iowa City through Illinois to South Bend, Indiana. (The next day’s Chicago Tribune referred to “stunning” overnight storm totals, up to 4.63 inches in Genoa, Illinois, and 8.34 inches in southeast Iowa’s Henry County—7.2 inches of it in four hours.) I-80 has a rural feel on this stretch. At one point the roof of a white barn appeared to be floating in the sky. I skipped the fast food chains in favor of a small diner with a prominent “for sale” sign out front, where I overheard a discussion about a woman who had quit working there to make more money driving a combine.

Edgar Lee Masters wrote a series of modernist poems about small towns like those I’ve glimpsed around here. His poems are framed as a series of unvarnished epitaphs, with an emphasis on excising hypocrisy. (Today you can get an RSS feed of his Spoon River Anthology here) Here’s Minerva Jones:

I AM Minerva, the village poetess,

Hooted at, jeered at by the Yahoos of the street

For my heavy body, cock-eye, and rolling walk,

And all the more when “Butch” Weldy

Captured me after a brutal hunt.

He left me to my fate with Doctor Meyers;

And I sank into death, growing numb from the feet up,

Like one stepping deeper and deeper into a stream of ice.

Will some one go to the village newspaper,

And gather into a book the verses I wrote?—

I thirsted so for love

I hungered so for life!

Indiana-born Theodore Dreiser’s Sister Carrie leaves her small Midwestern town for the city:

When Caroline Meeber boarded the afternoon train for Chicago, her total outfit consisted of a small trunk, a cheap imitation alligator-skinc satchel, a small lunch in a paper box, and a yellow leather snap purse, containing her ticket, a scrap of paper with her sister’s address in Van Buren Street, and four dollars in money. It was in August, 1889. She was eighteen years of age, bright, timid, and full of the illusions of ignorance and youth. Whatever touch of regret at parting characterised her thoughts, it was certainly not for advantages now being given up. A gush of tears at her mother’s farewell kiss, a touch in her throat when the cars clacked by the flour mill where her father worked by the day, a pathetic sigh as the familiar green environs of the village passed in review, and the threads which bound her so lightly to girlhood and home were irretrievably broken.

The local radio station broke the pastoral calm with a report police had shot a man in downtown Chicago. Bringing to mind Carl Sandburg of the Chicago poems and multi-volume Lincoln biography. Do Midwestern students still have to memorize his “Chicago?”

Hog Butcher for the World,

Tool maker, Stacker of Wheat,

Player with Railroads and the Nation’s Freight Handler;

Stormy, husky, brawling,

City of the Big Shoulders:

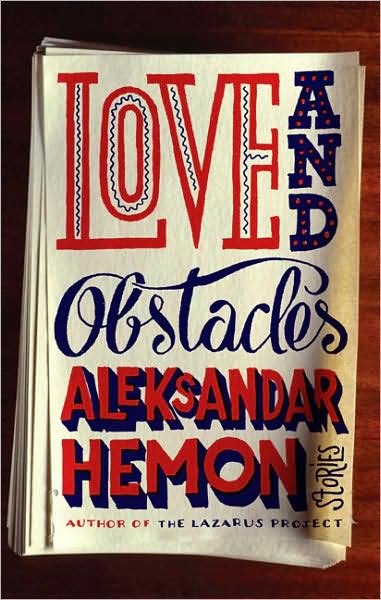

Sandburg was born in Galesburg, was first published in Harriet Monroe’s “Poetry” magazine. He won two Pulitzers in two genres—the 1950 Pulitzer for poetry and another for the second volume of his Lincoln biography. Nearly a century ago, Carl Sandburg, Edgar Lee Masters, Ben Hecht, Theodore Dreiser, and Sherwood Anderson were all part of a Chicago literary renaissance. The Sarajevo-born Aleksandar Hemon might have fit in with this crew. His NBCC fiction finalist “The Lazarus Project” was set during their heyday, and he has adopted Chicago as his hometown. I talked to him about Chicago earlier this year, upon the publication of “Love and Obstacles,” his short-story collection. He’s got a bead on some of the same issues, with his own sardonic twist.