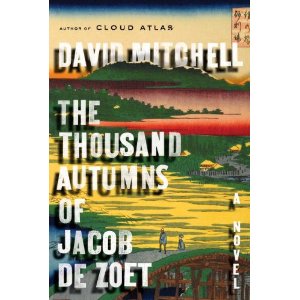

Ron Charles reviews David Mitchell's The Thousand Autumns of Jacob de Zoet in The Washington Post Book World:

In the first part of the novel, Mitchell spins out this ethical dilemma in careful — probably too careful — detail. Initially, the great cast of characters on the man-made island has just barely enough to do to keep the story moving forward, particularly one that rests on the ever-fascinating subject of accounting. But Mitchell is an author who deserves your trust, and he has constructed an apothecary cabinet of vibrant set pieces, including a beheading of petty thieves, a bladder-stone operation that will make you wince, and the arcane diplomatic rituals of meeting the shogun after “a ten-weeks' tributary arse-licking pilgrimage.”

For Bookslut, Kerri Arsenault reviews William Ayers's and Ryan Alexander-Tanner's To Teach: The Journey, in Comics:

The illustrations in To Teach, though rigorous, occasionally sweet, and sometimes funny, often do not enhance Ayers’s narrative, but instead mimic what the text already denotes. As early as page two, Ayers writes “Before I knew it, I was struggling just to keep my head above water.” Below the text is an image of Ayers’s head just above water. Had he ended the sentence, for instance, just after the word “struggle” and left the illustration to explain the rest, the frame would be more successful.

J. Peder Zane’s “Top Ten Books” blog, based on the concept behind his 2007 book, features Chad Post this week:

Since cutting his teeth at the Dalkey Archive Press, Chad, 34, has served as director of Open Letter Books at the University of Rochester, a relatively young press publishing only literature in translation. He is also the managing director of the Three Percent Website, which is one of the very best sources for information about international literature and the business of publishing. Three Percent is also home to the Translation Database (which tracks the publication of all original translation of fiction and poetry released in the U.S.), the Reading the World podcast series, and the Best Translated Book Award.

Jacob Silverman in VQR on Robert Walser’s Microscripts:

Walser called it his “pencil system” or “pencil method,” and it has also been described as “microscript” and “micrography.” Whatever the name, the writing technique entailed shrinking down letters to only 1 or 2 mm in height. Walser used Kurrent script, a medieval form of German writing that went out of fashion by the mid-twentieth century. The shrunken text allowed the writer to fit an entire short story on a business card, and he sometimes did so. In fact, he wrote on seemingly any available paper surface: postcards, telegrams, receipts, art paper, calendars, envelopes, and the torn-off covers of trashy novels (which he loved).

In the LA Times, Carolyn Kellogg reviews Role Models by John Waters:

The essays in “Role Models” meander pleasantly around personalities, recollections and ideas, always finding glory in the flaws. …Some of this is slightly familiar territory, as when he writes about Lady Zorro, a Baltimore stripper “so butch, so scary, so Johnny Cash,” mentioned in his 1987 book “Crackpot: The Obsessions of John Waters.” In “Role Models,” however, Waters discovers that she had a daughter, and he tracks the younger woman down to get her perspective. That he tells the story with honesty and compassion — an angry, self-destructive lesbian is less of a punch line when she's your mother — is what makes Waters special. Within his jokes and winks and countercultural jabs, he is striving for real human emotion. He is also kind.

Michael Orthofer’s review of The Pages by Murray Bail at the Complete Review is the 2,500th title under consideration at the website:

Bail, too recognizes that truths can be dug for (and found) endlessly, and instead of presenting as much as he might he offers in The Pages a novel that is little more than skeletal: a robust enough frame, but with little meat to it, leaving much for the reader to flesh out. It works quite well, for the most part, a novel cut nearly to the bone, but one might wish for there to be a bit more to it. Interestingly, it is less Wesley's philosophy one is more curious about — its fragmentary and ambiguous character work just fine — than his life, from the household he grew up in (where one still dressed up for dinner) to his years of wandering (only bits of which are described).

Bethanne Patrick is the Editor of The WETA Book Studio and a freelance critic.