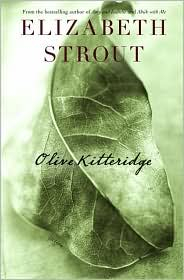

Each day leading up to the March 12 announcement of the 2008 NBCC awards, we highlight one of the thirty finalists. Today, NBCC board member Lizzie Skurnick discusses Elizabeth Strout’s Olive Kitteridge (Random House).

In literature, the unreliable narrator gets all of the attention—though far more interesting a creation is the truly unlikable narrator, to say nothing of one the reader still identifies and empathizes with, deeply. Such an animal is Olive Kitteridge, the heroine of Strout’s eponymous follow-up to her justly praised Amy & Isabelle. A series of brief sketches of the residents of a Maine town, Olive Kitteridge ducks the cloying school of small-town portraiture, instead using close-ups of Olive and her friends and relatives to tease away at the threads of anger, pettiness, and fear that can leave a life unraveled and unfulfilled.

Olive, a retired schoolteacher whose son lives in New York and whose pharmacist husband, we learn, lusts after his coworker, is as intemperate and moodily violent as Strout’s prose is lucid and remarkable. An aging woman given to mordant observations on her own now-loveless marriage, her distant son, and her life’s work, universally unhailed, she is the kind of mother who’s capable of secretly desecrating her daughter-in-law’s clothes with magic marker, for spite.

However, Strout is not interested in condemning Olive’s rage, or making it a comically overwrought co-character. The woman who is impatient with the idiocy of her neighbors, who cheers at their small setbacks, also saves a former student from driving himself off a cliff and attempts to force an anorexic girl to eat. But the part of Olive who chides her husband while they lie trussed on the floor during a stick-up, who is sad to realize her slight relief at his later death, who finds that she neither loves nor likes her son, is not any different from the part who weeps fitfully at a lost love of her own. Olive is impatient—with life, with grief, with happiness, with death—and her impatience occasions actions both beneficial and almost unbearable to those around her.

With Olive Kitteridge, we’re given a profound portrait of how seldom we actually rise to the occasion, how few breakthroughs we are allowed, how fleeting is happiness, how we are, at base, little more than squalling infants at life’s trials, fundamentally inconsolable. But Strout’s writing also has a deep vein of humor, a remove both wise and witty. How often does a novel feature an older woman—and an older woman who is bound to those around her at the same time she can’t help but fundamentally alienate them? I didn’t think anyone could mine anew the trope of the small town hiding its many miseries, but Strout’s masterful work remakes it, then transcends.