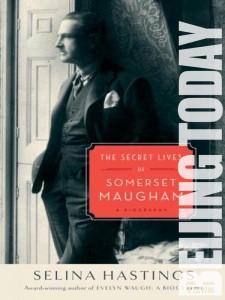

Each day leading up to the March 10 announcement of the 2010 NBCC award winners, Critical Mass highlights one of the thirty-one finalists (to read other entries in the series, click here). Today, NBCC board member Mary Ann Gwinn discusses biography finalist Selina Hastings's The Secret Lives of Somerset Maugham (Random House).

Each day leading up to the March 10 announcement of the 2010 NBCC award winners, Critical Mass highlights one of the thirty-one finalists (to read other entries in the series, click here). Today, NBCC board member Mary Ann Gwinn discusses biography finalist Selina Hastings's The Secret Lives of Somerset Maugham (Random House).

One can only wonder at the conversations British biographer Selina Hastings had with herself as she weighed writing a new biography of the British author W. Somerset Maugham (1874–1975). Would she ever sort out Maugham’s complicated personal life? Get to the nub of his ambivalence toward his friends and family? Adequately capture the life of a man, who, according to The Telegraph’s review of Hastings’s The Secret Lives of Somerset Maugham, “was a slum doctor, an Edwardian man of fashion, a playwright with a string of hits, a best-selling novelist, a secret agent in Russia, a world traveller, an art collector and philanthropist”?

Hastings, a biographer of other complicated people (Evelyn Waugh, Nancy Mitford) did sort it out and has produced a masterful biography of a man who was often compromised by his passions and his loyalties but who never wavered from his devotion to the art and craft of writing.

Born in Paris to a British expatriate family, Maugham’s idyllic childhood was effectively destroyed when, at age 8, his adored and adoring mother died. His father became ill and eventually shipped the young boy and his brothers back to England; the brothers were old enough to attend school, but Maugham landed with his “snobbish, blinkered and magnificently self-centered” uncle, an English vicar.

His aunt and uncle (who would later show up in Of Human Bondage) tried to be kind, but the young Maugham was devastated. In this alien household he developed a stutter but also the lifelong habits of an acute observer––listen and watch. These were skills that would serve him both as a writer and a spy–– Maugham worked for British intelligence during World War I, an interlude that would result in Ashenden, a collection of spy stories that would later turn into a Hitchcock film (Secret Agent, starring John Gielgud and Peter Lorre).

His first professional conflict was between his training as a doctor and his yearning to write. Writing won out; Maugham published a series of increasingly successful stories, novels, and plays. The plays, English drawing-room comedies, were enormous moneymakers which funded his more ambitious stories and novels. Maugham became world-famous. “His books were translated into almost every known tongue, filmed, dramatized, and sold in their millions, bringing him celebrity and enormous wealth,” Hastings writes.

The money also allowed him to travel and manage the complications of his personal life. Maugham was primarily attracted to men, though early on he did have affectionate affairs with women. But his relationship with his wife, Syrie Wellcome, was anything but a love affair––Wellcome trapped Maugham into marriage by getting pregnant. To escape from Syrie and gather material for his books, Maugham traveled the length and breadth of the British empire, frequently in the company of “dissolute charmer” Gerald Haxton, his lifelong lover. The two used and abused each other, but their attraction never faltered, and Maugham devoted himself to Haxton for the rest of Haxton’s life.

Maugham was a “passionate, difficult man, capable of cruelty as well as of great kindness and charm,” Hastings writes. His hatred for Syrie and his discomfort with his fatherly obligations to his daughter Liza call to mind the famous Sartre line in No Exit: Hell is Other People. Maugham’s central loyalty was to his art––though relationships might fall by the wayside, he never wavered or compromised his dedication to his stories and novels, unflinching portraits of human passion and frailty. Though Maugham derided his own work as “in the very front row of the second rate,” his friend Desmond MacCarthy got it right about his work: “at his best he can tell a story as well as any man alive or dead.”

Hastings’s portrait is brisk but not dismissive, judicious but not judgmental. You can read The Secret Lives of Somerset for its portrait of an age, for its delicious literary gossip, or for its evocation of the homosexual demimonde that flourished before, during, and after World War II. But most of all, read it because it’s an indelible portrait of a writer––an activity as necessary as breathing for Somerset Maugham, and the secret at the center of all his lives. Hastings tells his story with grace and sympathy.

To read an excerpt from The Secret Lives of Somerset Maugham (via nytimes.com), click here. Click here to access Selina Hastings's website.