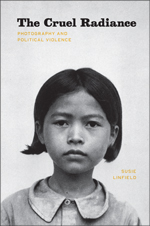

Each day leading up to the March 10 announcement of the 2010 NBCC award winners, Critical Mass highlights one of the thirty-one finalists (to read other entries in the series, click here). Today, NBCC board member Scott McLemee discusses criticism finalist Susie Linfield's The Cruel Radiance: Photography and Political Violence (University of Chicago Press).

Each day leading up to the March 10 announcement of the 2010 NBCC award winners, Critical Mass highlights one of the thirty-one finalists (to read other entries in the series, click here). Today, NBCC board member Scott McLemee discusses criticism finalist Susie Linfield's The Cruel Radiance: Photography and Political Violence (University of Chicago Press).

The essays in Susan Sontag’s On Photography––winner of the NBCC award for criticism in 1977––added up to an indictment of the role of the camera in the way we live now. Photography, her argument went, fragments the world: its destroys context, turning experience into so many virtual commodities that we appropriate (by “taking” pictures) as much as we feel or understand them.

In Regarding the Pain of Others––the last major work Sontag published before her death in 2004, the same year the book was named an NBCC finalist––her old complaints were revisited and reconsidered, though not completely withdrawn. While acknowledging that depictions of war and disaster play a more complex moral and political role than her earlier thesis might allow, she remained skeptical of the lust for imagery.

Susie Linfield’s The Cruel Radiance: Photography and Political Violence is, to put it one way, anti-Sontagian. Photojournalism can inform the public’s moral sense, as well as its need for news — and despite the common assumption that images of death and destruction have a numbing effect, Linfield finds that they exercise power precisely through their emotional resonance.

But photography criticism – from Baudelaire to the Frankfurt School on to postmodernism — has cultivated a sort of cold suspicion of affect and of the medium itself. Critics working in that vein “view emotional responses – if they have any – not as something to be experienced and understood but, rather, as an enemy to be vigilantly guarded against. For these writers, criticism is a prophylactic against the virus of sentiment, and pleasure is denounced as self-indulgent.”

Unable to find a usable tradition in photography criticism itself, then, Linfield draws on the example of James Agee’s and Pauline Kael’s writings on film, and Kenneth Tynan’s on theater. “Their starting point was, always, their subjective, immediate experience,” Linfield says, “which meant that they had to be honest with themselves. … For such critics, emotional reactions and critical faculties weren’t synonymous, but they weren’t opposites, either. These critics sought, and achieved, a fertile dialectic between ideas and emotions: they were able to think and feel at the same time, or at least within the same essay.”

Linfield writes about imagery from numerous scenes of political violence (among them the Spanish Civil War, Auschwitz, Chechnya, and Abu Ghraib) and reflects on whole bodies of work by Robert Capa, James Nachtway, and Gilles Peress. Her political stance is marked, clearly enough, as belonging to what is sometimes called humanitarian-interventionist liberalism, of the sort associated with George Packer, Bernard-Henri Lévy, and, in her final years anyway, Sontag herself.

Linfield avoids any tendency to wax metaphysical on the essence of photography or the ontological status of “the image.” Instead, her attention goes to describing and assessing particular photographs (an effort inseparable from describing and assessing the realities they record) while grappling with her own feelings while looking at them.

Just because she recognizes the power of photojournalism does not mean she is a sentimentalist. The most interesting moments in The Cruel Radiance involve fairly ambivalent responses, or feelings that can be painful to acknowledge. Photographs from the Holocaust would be easier to confront if they simply evoked moral indignation or rage at the perpetrators. But when the Nazis themselves were wielding the camera, the images not only record the atrocity but celebrate it, or at least treat it as something matter-of-fact and morally unproblematic. The viewer is meant to be complicit. Which is bad enough, but Linfield also admits that such “photographs of bottomless, impotent suffering” sometime leave her impatient with the victims. Scarcity of images of resistance makes the degradation seem profound, even absolute.

There is criticism that judges a work or scrutinizes its form––and then there is criticism that tries to engage the whole field of experience involved in the work, the way it enters life (including the audience’s sense of reality) and remakes it. Linfield’s book belongs to the latter category. Images of political violence, if not political violence itself, are part of everyone’s experience. The Cruel Radiance is a lesson in the complexities of response involved in looking at them––or, sometimes, turning away.

Susie LInfield's home page at NYU can be accessed here. To read an excerpt from The Cruel Radiance, click here.