In the weeks leading up to the March 12 announcement of the 2014 NBCC award winners, Critical Mass highlights the thirty finalists. Today, NBCC board members Tess Taylor, representing the poetry committee, and Walton Muyumba, chair of the criticism committee, offer an appreciation–a dialogue of sorts–of Claudia Rankine's “Citizen,” (Graywolf Press), which made NBCC history when the board voted it a finalist in two categories–criticism and poetry.

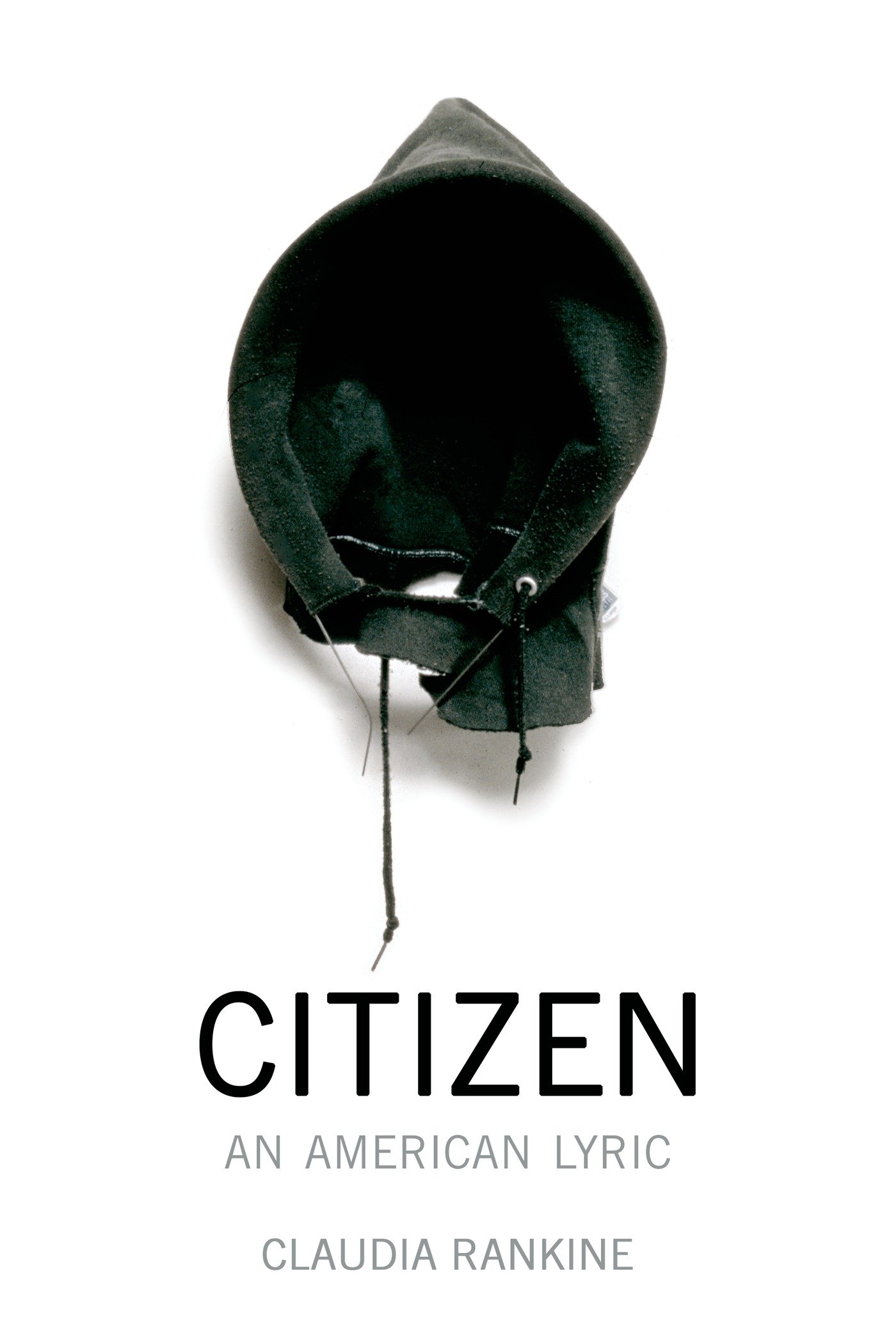

Since the shooting of Trayvon Martin and the death of Michael Brown, since the unrest in Ferguson, and right now, at the moment when we await judgments facing the police officers who shot Tamir Rice, we keep watching the painful spectacle of seemingly sanctioned violence against black bodies. These men’s deaths announce and re-announce painful questions: Do we live in a country in which the lives of black men matter less than the lives of white ones? In which ways does racial violence persist to this day? What does it feel like–for any of us–to live in the presence of disparity overwhelmingly marked along racial lines?

These are large questions. What Claudia Rankine’s book “Citizen” does, miraculously, is break racism’s intractability down into human-sized installations, accounts of relationships, and examples of speech. These pieces, which can equally be read as prose poems or as micro essays, map the uneasiness and charged space of living race now.

In her explorations, Rankine is at once fierce and enormously compassionate. There’s violence here, and blunder; there’s pain, and the desire to connect; there’s the horror of encountering racism both in its intended and in its disturbing, unattended moments. “The route is often associative,” writes Rankine in one of her poems, but she leaves each of us to reflect on what basis we–any of us–associate? “Certain moments send adrenaline to the heart,” Rankine writes in another piece, but why, and how do any of us learn fear?

Defying genre, Rankine’s meditations straddle the line between diagnosis and description, between essay and poem. They often address a “you” who–no less than the figure in a Renaissance poem–is the invisible but longed for object of great desire. In this case, the desire is that “you” –both Rankine’s unseen readers, and the culture at large — examine ourselves, “acknowledge” our “slippage,” and “dodge the buildup of erasure.”

“Citizen” is about blackness, but it is also about whiteness; it speaks to current events, but it is also traces imaginaries. It uses the realm of the lyric to critique the terms by which we live. In “Citizen,” our bodies and our racial selves are not isolated or even present tense, but also communal, unconscious, historical. “This is how you are a citizen,” Rankine writes. “Come on. Let it go. Move on.”

But what does it mean to move on? How should we move? Rankine leaves this question open, pulling us in and asking us to keep thinking about it. She notes that “All our fevered history won’t instill insight, won’t turn a body conscious, won’t make that look in the eyes say yes.” But she also challenges us all when she writes “each moment is an answer.”

–Tess Taylor

Early in “Citizen”, Claudia Rankine asks, “What does a victorious or defeated black woman’s body in a historically white space look like?” Though she’s recalling Serena Williams’ infamous outburst during the 2009 US Open women’s semifinal, Rankine might well be asking about her own body and writing in American culture. Her question also sounds like the large questions we’re currently asking about the worth of black American lives. These questions are as old as the nation itself, but they probably seem more pressing now because we have access to an ever-expanding video catalog of black lives not mattering, black lives policed without equal protection, and black lives dashed matter-of-factly in 21st century America.

For some, the footage of Marlene Pinnock’s roadside beating or John Crawford’s (or Eric Garner’s or Tamir Rice’s) final moments of life is heart-rending evidence of things they’d rather have remain unknown and unseen: the lethal finality of anti-black racism. For Rankine, as with many other African Americans, those videos document what we’ve always known about the meaning of being black in public spaces: the black body is invisible and “hypervisible” simultaneously. “Citizen” is Rankine’s index of the psychological damages that come along with navigating American life in these concurrent states.

While videos can display mortal blows, “Citizen” charts constellations of seemingly innocuous exchanges and experiences that injure black people psychologically and emotionally. The worst of these injuries, Rankine explains, leave you feeling that “you don’t belong so much to you –.” “Citizen,” then, is a blues book; it’s a “worrying exhale of an ache.” Rankine probes the black body’s grievous wounds, improvising on, revising, and thus extending the intellectual and artistic genealogy listed at the end of “Citizen” — Patricia Williams, Carrie Mae Weems, James Baldwin, Frantz Fanon, Lauren Berlant, and Ralph Ellison, among others.

Rankine composes music – “the dissolving blues of metaphor” – through formal indeterminacy. She worries the fine lines delineating lyric from essay, first person exposition from second person address, glossy art exhibition catalog from literary artwork, poetry from criticism. Taking cut-outs from her experiences, she collages those pieces (like Romare Bearden, a blues improviser in his own right) into “Citizen”’s seven sections – she’s fitted her personal history to the American present.

Maybe, then, “Citizen” is also about whiteness in the same way that all American moments have been about whiteness. If we’re trained to understand that the ideal American citizen has a white body, then Rankine’s sense, that citizenship is about letting go of or moving on from racial injury, seems right. But her conception is really an indictment of the voice speaking throughout “Citizen” and the reader, both of whom want, for instance, to get over, to let go of, to move on from the sight of some black boy’s body bleeding out, a toy gun, or cheap cigars, or bag of candy lying prone and meaninglessly nearby.

But this, as Toni Morrison would say, is not a thing to pass on. Rankine’s work provokes you to envision your American life as wedded to the well-being of the black body. And what drives you to accept “Citizen”’s challenge is a desire to comprehend blackness, its power and resiliency even in injury. Rankine’s rendering of black invisiblity/hypervisibility is akin to Glenn Ligon’s piece, “Untitled (I Feel Most Colored When I Am Thrown Against a Sharp White Background).” She’s placed a detail from this artwork in the third section of “Citizen.” Ligon’s subject and title come from a line in Zora Neale Hurston’s essay, “How it Feels to be Colored Me.” Ligon stenciled the line on canvas and then used smudging oil sticks and graphite “to transform the words into abstractions.” Though Rankine recognizes Hurston’s line as “ad copy for some aspect of life for all black bodies,” what she’s after throughout “Citizen” is a route away from hypervisible/invisible blackness in white spaces toward a vision of black human experience as something like smudged abstraction.

To realize this final vision, where each moment is an answer, you have to pass through the facsimile of Wangechi Mutu’s gorgeous, disturbing, “Sleeping Heads.” Rankine has inserted Mutu’s mixture of painting and collage in the book’s final section to sit as a pictorial simile for “Citizen.” Like the hands in Mutu’s image, Rankine’s poetry, image curating, and cultural criticism take you by the neck, put you “in a chokehold, every part roughed up, the eyes dripping,” and pull you into the smudged abstraction, what Elizabeth Alexander calls, the black interior, where you might recognize yourself. What James Baldwin once wrote about Beauford Delaney’s paintings, you can also address to Rankine’s art in “Citizen”: her “work leads the inner and outer eye, directly and inexorably, to a new confrontation with reality. At this moment one begins to apprehend the nature of [her] triumph. And the beauty of [her] triumph, and the proof that it is a real one, is that [she] makes it ours.”

–Walton Muyumba

Reviews:

The New Yorker review.

Review in The New York Times Book Review.

Slate review.

Flavorwire review.

Bookforum review.

Interviews:

Los Angeles Time interview.

Interview, The New York Times.

NPR's Weekend Edition interview.

And a Slate piece about the changes made in the various reprintings of 'Citizen.'