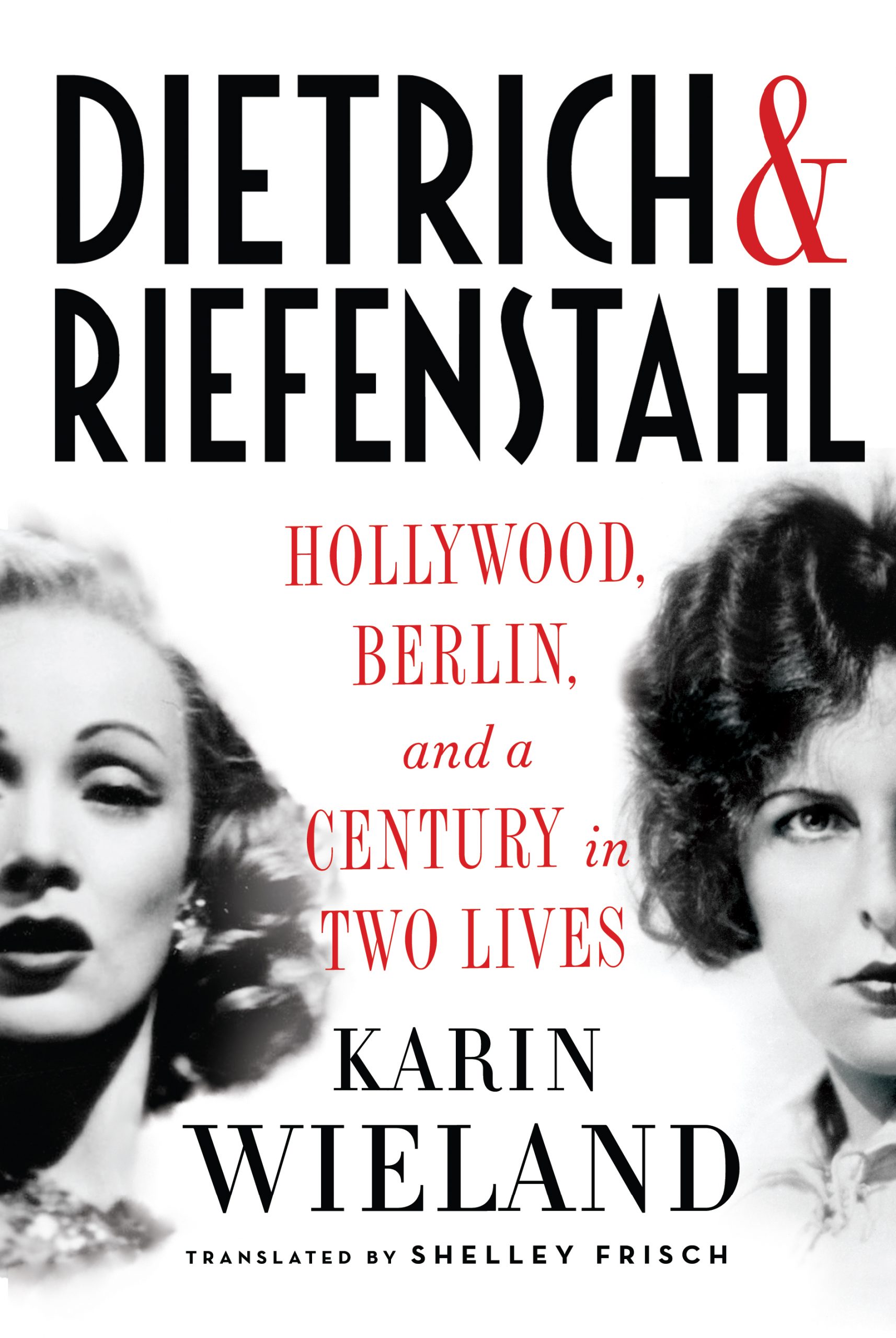

In the days leading up to the March 17 announcement of the 2015 NBCC award winners, Critical Mass highlights the thirty finalists. Today, NBCC board member Kate Tuttle on biography finalist “Dietrich & Riefenstahl: Hollywood, Berlin, and a Century in Two Lives” by Karin Wieland, translated by Shelley Frisch (Liveright).

Born within a year of one another, Marlene Dietrich and Leni Riefenstahl were Berliners of the same generation. Each, in her own way, broke free from convention to seek expression in the arts; both left their mark as aesthetic icons. Today, while we remember Dietrich for her languid, transgressive glamor (including the monocle she wore, a hand-me-down from her late aristocratic stepfather), Riefenstahl’s legacy as the filmmaker responsible for Hitler’s cinematic brand is ugly. Karin Wieland braids together the lives of these two women in a thoughtful yet deliciously gossipy dual biography.

They had much in common. Each was born into a family anxious about its social status – the Riefenstahls doggedly climbed toward a middle-class life, while Dietrich’s mother married into a fading aristocracy that would forever color her daughter’s worldview. And both grew up in a city still reeling from the losses of World War I, buffeted by crosscurrents of modernism and reactionary fascism.

“Dietrich was raised for a world that was coming apart,” Wieland writes. Her childhood idol was her grandmother, a gracious beauty who loved flowers, jewels, and French fashion magazines. When the war brought poverty, death, and chaos, a teenaged Dietrich responded with hard work and focus; Wieland notes, “as a child of the war who had been raised in the Prussian spirit, she had learned above all how to get by.” An indifferent student, impatient to get on with life, Dietrich settled on acting as a way “to enjoy pretty things and make a good living while doing so.” She had beauty but, at first, no talent. What she had was ambition and an almost superhuman persistence.

Leni Riefenstahl’s ambition was equally fierce. Her parents provided dance and music lessons so that their daughter would do well on the marriage market, continuing their upward march into bourgeois comfort, but they were not happy with her aspiration to fame as an avant-garde entertainer. Like Dietrich, Riefenstahl lacked natural talent; rather than push harder, her strategy was to move forward and then rewrite the past. Wieland notes her fabulist tendencies, but also her powerful charisma, which enabled her to assemble a powerful circle of supporters. After failing at dance and acting, Riefenstahl became a filmmaker working on a strange Teutonic genre of moviemaking known as the mountain film – snowy epics of skiing, climbing, and danger.

The rise of Nazism is where the two women’s stories diverge. Dietrich emigrated to Hollywood for work in the early 1930s and refused to return to Germany under Hitler. Riefenstahl used the power of cinematic technique to sell Hitler to the masses; along the way, she entered Hitler’s inner circle. (Even they thought she worked too hard: upon seeing her as she completed “Triumph of the Will,” Nazi propaganda minister Goebbels wrote in his diary, “She simply has to take a vacation.”) Dietrich, who never stopped mourning the evil her fatherland had committed, endured long periods of illness and solitude before dying in Paris in 1992. Riefenstahl never disavowed Hitler, nor did she abandon her lifelong habit of dissembling, misrepresenting, lying. She died at 101, a celebrity, as she had wanted.

Wieland treats both women with compassionate sympathy, but she doesn’t shy away from the clear-eyed assessment they each deserve. In the end, looking at these two lives side by side, the book invites readers to ponder some of the big questions raised by all of 20th-century history: what is the legacy of war, how can art provide solace, and how, in the end, are we to live in the shadow of evil?

Review: New York Times

Review: Washington Post

Review: New Yorker