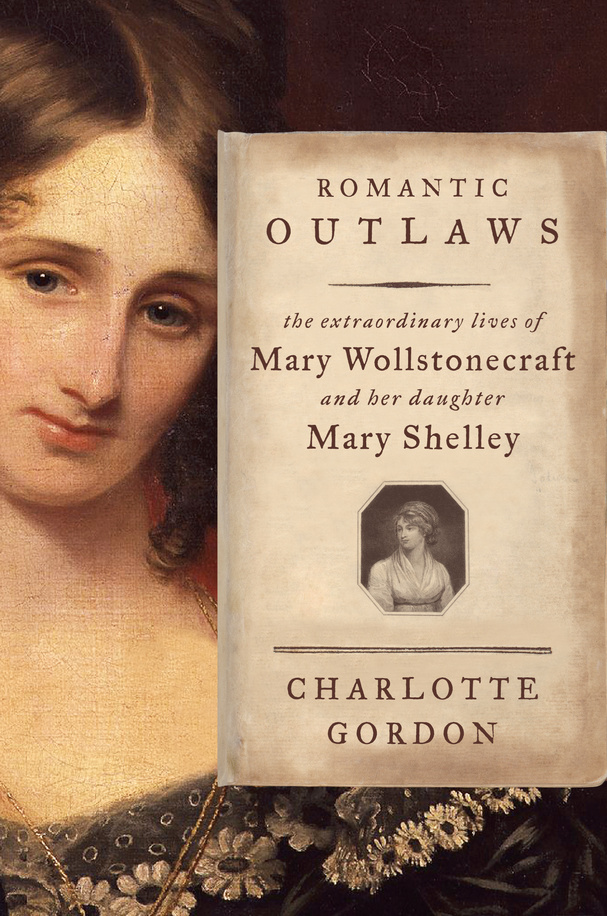

In the days leading up to the March 17 announcement of the 2015 NBCC award winners, Critical Mass highlights the thirty finalists. Today, NBCC board member Katherine A. Powers on Charlotte Gordon's “Romantic Outlaws: The Extraordinary Lives of Mary Wollstonecraft and her daughter Mary Shelley” (Random House).

Charlotte Gordon's “Romantic Outlaws: The Extraordinary Lives of Mary Wollstonecraft and Her Daughter Mary Shelley” makes an unusual and character-rich addition to the already well-stocked shelves of books about these two talented, unconventional women. It covers their lives and work in alternating chapters to reveal not only their individual personalities, but also their intellectual proclivities and manner of life as ideal and emulation, and as a continuum of social rebellion and its personal repercussions.

Wollstonecraft grew up with a violent, dipsomaniac father; a despondent, violated mother; and numerous siblings, among whom only the boys were granted formal education. Gordon follows her subject as she seizes her own life to the extent that she could, becoming a paid companion, governess, and eventually teacher, running a school with her two resentful, discontented sisters. In time, Wollstonecraft was able to make an independent living by her pen with reviews, articles, and books, most notably “A Vindication of the Rights of Women.” That work and her later “Letters Written During a Short Residence in Sweden, Norway and Denmark,” which influenced Coleridge, made Wollstonecraft a pioneer in feminism and Romanticism—to say nothing of freelance survival.

An unhappy affair produced a daughter, Fanny, and left Wollstonecraft socially ostracized, a condition only partly ameliorated by her marriage to William Godwin. Though the couple had individually opposed marriage in their writings, they entered it because Wollstonecraft, pregnant again, hoped to escape further castigation of herself and her unborn child. She died of puerperal fever 11 days after the birth of Mary, leaving Godwin with the infant and her half-sister Fanny.

Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin Shelley grew up nourished by her mother's writings and happy enough until her father married a woman who came with two daughters and a predisposition to snub Mary and Fanny. At 16, Mary ran off with the married, 21-year-old Percy Bysshe Shelley. The couple took along Mary's stepsister, Claire, the result being that the ménage and its companions, which included Lord Byron and other writers and exotics, were labeled a “league of incest” by scandalized observers. To Mary's dismayed surprise, her father, once an advocate of free love, broke off communication with her—though he continued to pester Shelley for money. Gordon suggests convincingly that Mary's shock at Godwin's rejection, her sense of motherlessness, and her abhorrence of man's craving for boundless power found artistic expression in her novel “Frankenstein,” a work begun in the summer of 1816 on Lake Geneva in the company of Shelley, Byron, and others.

Mary's years with Shelley were made up of travel, writing, passion, grief, and anger. Death struck hard: babies and children, hers and Claire's, died from disease and other natural causes; her half sister, Fanny, and Shelley's first wife took their own lives. Finally, Shelley drowned, leaving Mary—who had become embittered and alienated from him—a remorseful widow at 24. Outside of Anne Boleyn and Elizabeth I, Mary Wollstonecraft and Mary Shelley are perhaps the world's most famous mother-daughter eminences, and Charlotte Gordon has served their lives extraordinarily well. Her tandem biography illuminates the society they lived in and rebelled against, and seats the two women firmly in the world of ideas.

The Guardian – Daisy Hay

Boston Globe – Matthew Price

The Independent – Shirley Whiteside