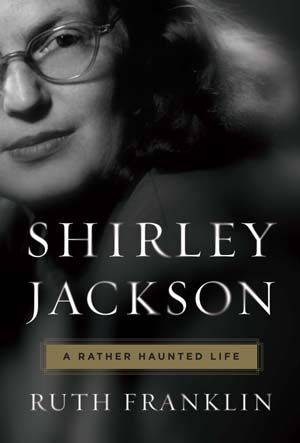

In the 30 Books in 30 Days series leading up to the March 16 announcement of the 2016 National Book Critics Circle award winners, NBCC board members review the thirty finalists. Today, NBCC board member Kate Tuttle offers an appreciation of biography finalist Ruth Franklin’s Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life (Liveright).

In the 30 Books in 30 Days series leading up to the March 16 announcement of the 2016 National Book Critics Circle award winners, NBCC board members review the thirty finalists. Today, NBCC board member Kate Tuttle offers an appreciation of biography finalist Ruth Franklin’s Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life (Liveright).

Shirley Jackson became famous in midcentury America for her short story “The Lottery,” which unnerved readers from the moment it appeared in the New Yorker in 1948, and for a string of gothic novels, as well as her cheerful yet brutally honest essays about juggling four kids, pets, a house, and a husband. In this biography, Ruth Franklin gets at what makes Jackson both sui generis and familiar. Jackson’s fiction, Franklin argues, deserves to be considered as part of the “vibrant and distinguished tradition that can be traced back to the American Gothic work of Nathaniel Hawthorne, Edgar Allan Poe, and Henry James.” Jackson’s particular attention to women’s stories, along with her nonfiction work, mostly for women’s magazines, may have contributed to her unfairly diminished reputation as a serious literary writer. Franklin’s telling of Jackson’s life story is sensitively written and extremely absorbing; it also makes a persuasive case for readers to revisit and reconsider this important American writer.

The difficulty of being a woman and a writer is neatly illustrated in one anecdote Franklin tells in the book’s introduction. Arriving at the hospital to deliver her third child, Jackson is met by a clerk filling out paperwork. Asked for her occupation, she says she’s a writer. “I’ll just put down housewife,” the clerk replies. Born in 1916 to an English immigrant father and a San Francisco socialite mother, Jackson grew up in a family that didn’t encourage her literary pursuits – indeed, her scathingly critical mother didn’t seem to encourage her in much of anything. Jackson’s son recalls his grandmother as “a deeply conventional woman who was horrified by the idea that her daughter was not going to be deeply conventional.”

Jackson began writing as an unhappy high school student in Rochester, New York, where her family had moved from California. It was at Syracuse, where she was midway through her college career, that her future as both a writer and a housewife began. There she met Stanley Edgar Hyman, who would become a literary critic, professor, and her husband. Their life together was complicated; though they “shared an intellectually rich marriage and a warm family life,” Franklin writes, “he could be a domineering and sometimes unfaithful partner.” Her earliest reader and cheerleader, Hyman also resented Jackson’s literary success and undermined her confidence repeatedly. Jackson endured his flirtations and affairs with other women, including students. She felt alienated among the suburban women around her – part of the inspiration for “The Lottery” – and to some extent remained an outsider in the literary world. She suffered crippling anxiety, which morphed into full-blown agoraphobia in the final years of her life. The world Jackson lived in expected very little of her, but she managed to get an extraordinary amount of writing done before dying in 1965, at just 48.

Franklin writes with both authority and compassion about Jackson as both writer and woman. A good biography is always entertaining, and a great one – such as this – helps us understand the subject's era, her passion, her work, and something of her soul.