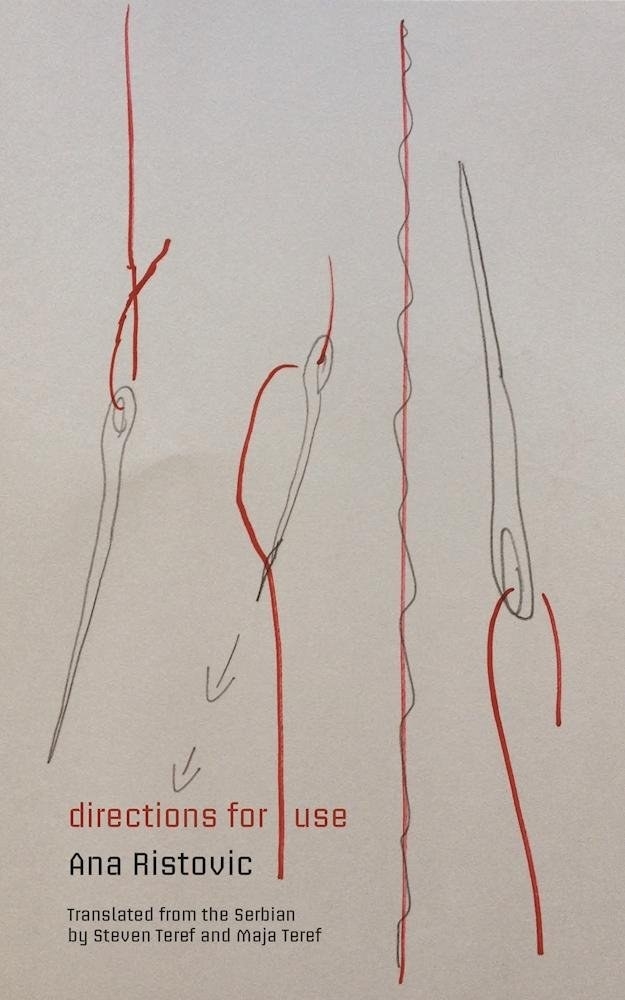

In the 30 Books in 30 Days series leading up to the March 15 announcement of the 2017 National Book Critics Circle award winners, NBCC board members review the thirty finalists. Today, NBCC board member Daisy Fried offers an appreciation of Ana Ristovic’s 'Directions for Use' (Zephyr Press)

Serbian poet Ana Ristovic is author of nine books of poetry. Not much known in our sometimes self-absorbed American poetry circles, she has been awarded Germany’s Hubert Burda Preis for younger European poets, and the Disova Nagrada, one of the most prestigious Serbian poetry prizes.

Serbian poet Ana Ristovic is author of nine books of poetry. Not much known in our sometimes self-absorbed American poetry circles, she has been awarded Germany’s Hubert Burda Preis for younger European poets, and the Disova Nagrada, one of the most prestigious Serbian poetry prizes.

In Steven and Maja Teref’s translation, Ristovic’s poems are wryly feminist, darkly exuberant, fascinated by commodities and focused on the body. In “Barcode Girl” a friend has a barcode tattooed on her back. “…every other word from her/ is my worth, I value, and at the cost of…” The store alarms her tattoo sets off are “Beethoven’s ‘Eroica’to her ears/or the cry of a gull swooping/on a landfill.” Into a comic situation comes great music, and the elsewhere of gull and landfill—becoming huge, concerning human plight.

Ristovic’s tonal shifts are immense. “Circling Zero,” begins in declaration (“We are independent women”), and ends intimately, elegantly describing masturbation (“And we smile with sadness in dreamless dreams./And the safe hand, circling/the soft zero.”) Talking about God in “Black Radish,” she’s casual, and not merely irreverent: “I grate a black radish/as God grates snow…//He and I/grate one another,/until exhausted/by the same/hunger.”

Imagining poets on World Poetry Day, in “Beware, Poet!” “flooding the streets like Hitchcock’s birds,” she imagines bumping into them at the supermarket. “Salt will turn Biblical./At the butcher counter, every slab of meat my body./And every bone, a quotation about Adam’s Rib.” Later she subsides, sort of:

After such an ordeal,

I’ll stand before my oven

like Sylvia Plath.

But, I’ll rethink

what to stick in it.

Many American poets wouldn’t say something like that, more’s the pity. Which means they couldn’t lead us to the particular places of hilarity and epiphany that are all Ristovic’s own.