This is the fifteenth in Critical Mass's new Second Thoughts series, curated by Daniel Akst. More about this series, and how to submit, here.

When I was a girl, I would play with my father’s books. He gave me permission to make a series of small slash marks on their inside covers, marks that doubled as bar codes and would be “scanned” under the imaginary laser of my toy microscope when I played library. When I was old enough for junior high school, I went from librarian to schoolteacher. This meant I would sit in my basement in front of a classroom of imaginary students and read aloud from those same books.

My dad was a lover of American poetry, but when I was 11 or 12, there wasn’t much I could understand from his poetry books. So what made the biggest impression were poems that evoked something in me through their music, even if their sense was just beyond my grasp. The poems that rhymed were gut-familiar to me. Theirs were the rhythms and structures we grow up on: the gallop of iambic pentameter, the satisfaction of a rhyming pair. Yet I also loved the thrill of not knowing precisely what the poems said. That mystery is what made me begin to copy some of them into a little notebook I kept for the purpose. I came to many poets in this space of half-play, half-incantation. Dickinson. Poe. Plath. And Adrienne Rich.

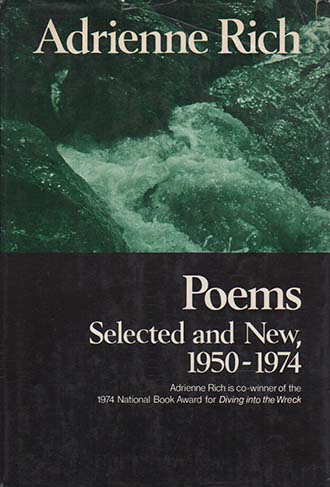

The Rich book my father had was Poems: Selected and New 1950-1974. The poems that drew me then were Rich’s earliest. I read, again and again, “Aunt Jennifer’s Tigers,” a frequently anthologized poem from Rich’s 1951 debut, A Change of World. The imagery was obscure to me:

Aunt Jennifer’s tigers prance across a screen,

Bright topaz denizens of a world of green.

They do not fear the men beneath the tree;

They pace in sleek chivalric certainty.

I didn’t know anything about needlepoint back then, nor did I know what “chivalric certainty” meant, so this stanza was largely lost on me. But there was nothing difficult about the couplet that closes the second stanza:

The massive weight of Uncle’s wedding band

Sits heavily upon Aunt Jennifer’s hand.

This was the first time I could remember reading about someone in an unhappy or oppressive marriage. My parents were still together, as were my grandparents and all but one of parents’ siblings. But here was Aunt Jennifer, whoever she was, under the weight of that wedding ring and that heavy, heavy rhyme. And whatever the tigers were doing, that wasn’t good either.

But the Rich poem that I copied into my little black book wasn’t brief like “Aunt Jennifer’s Tigers.” It was called “Stepping Backward” and it stood out from the rest of the poems in A Change of World as sprawling, rhetorical, unrhymed. What drew me to it? In part, it was the lilt when I read it out loud, a lilt that I now recognize as blank verse. Also, its arresting opening:

Good-by to you whom I shall see tomorrow,

Next year and when I’m fifty; still good-by.

This is the leave we never really take.

Why was the speaker saying farewell to someone she would see the next day? The rest of the poem’s exploration came to me in fragments when I was 12, highlighted by the moments in the text that stood out as stark declaratives or imperatives. “They’re luckiest who know they’re not unique,” the speaker says. Later:

Let us return to imperfection’s school.

No longer wandering after Plato’s ghost,

Seeking the garden where all fruit is flawless,

We must at last renounce that ultimate blue

And take a walk in other kinds of weather.

These lines carried me through the difficulties and loneliness of adolescence. Allow people to be who they are, the poem seemed to say. Celebrate their imperfections; don’t demand too much. Empathize. Feeling that you are special leads to exceptionalism. Exceptionalism is dangerous.

As the years went by I earned a PhD in poetry, and different Rich poems became important to me for different reasons. But these were her later works, and I read them with the full knowledge of her history: her mothering of three sons, her husband’s suicide, her radical politics, her lesbianism. I remember being thunderstruck by her “21 Love Poems,” explicit in their sexuality, but tender. I memorized “Power,” Rich’s poem about Marie Curie, which ends:

She died a famous woman denying

her wounds

denying

her wounds came from the same source as her power.

Rich seemed to me to hold that same kind of power: electric, but also slightly terrifying.

What I didn’t see until I went back to that first volume I encountered, the Poems: Selected and New 1950-1974, is that this power was always there in Rich. The book, read whole, shows the arc that I missed as a young girl. First, there is the obvious: in concentrating on her more musical early works, I had ignored what was there at the end of the volume, 20 years in the future from Rich’s debut collection. Where Aunt Jennifer had to stand in for the unhappily married woman in the early work, Rich takes on the role in the 1974 poem “For L.G.: Unseen for Twenty Years.” The two decade mark is notable: we are going back to when Rich was writing her first books. The poem is addressed to a man who appears to be struggling with his masculinity and his sexuality; the speaker remembers the assurances she tried to give him 20 years ago:

The one night in all our weeks of talk

you talked of fear

I wonder

what words of mine drift back to you?

Something like:

But you’re a man, I know it—

the swiftness of your mind is masculine—?

—some set-piece I’d learned to embroider

in my woman’s education

while the needle scarred my hand?

Here is Aunt Jennifer’s sewing needle again, wielded this time by a speaker Rich invites us to see as herself. From the perspective of time, she sees that she and this man had been alike, both of them unsure, in the early 1950s, of how to cope with the gender norms of their times, yet lacking the vocabulary to talk about the problem. One thing that has come to pass in the intervening years: Rich can speak it out, as herself.

I can see now the anger that even the early poems have, the tension that strings the poems tight as Rich balances their reassuring rhyme and meter against protests surging beneath. We see this same trajectory in many female poets of that era, from Sylvia Plath to Anne Sexton to Rich. Early poems are formal, with a high degree of restraint, later cracking open to still highly-crafted, but looser, rawer, more direct utterances. We can link this, of course, to changes in the political climate, to the women’s movement and the rise of feminism. And we root for the poems to crack free of their formal strictures because we know the consequences for women. It is no coincidence that so many young female poets hold up Rich, Sexton, and Plath as models: these are the poets that taught us how to seize permission to speak.

Though so many of Rich’s poems are about investigating her identity as a woman, “Stepping Backward,” the poem I copied into my little book, is even more fundamental.

You asked me once, and I could give no answer,

How far dare we throw off the daily ruse,

Official treacheries of face and name,

Have out our true identity?

The poem’s answer is that our true selves can only be displayed when we abandon self-consciousness and reserve. When Rich states, “They’re luckiest who know they’re not unique,” she follows by saying, “But only art or common interchange / Can teach that kindest truth.” Art reminds us that we aren’t special—or, put another way, that we aren’t alone. And common interchange, when we allow for others’ flaws and have compassion for “our blunders and our blind mischances,” is what allows us to truly see each other. This is the truth I understood, at least partly, even playing schoolteacher in my childhood basement. But I now think I understand the reason for the speaker’s farewell, the meaning of which eluded me when I was young. She wants to make a ceremony of her leave-taking so that she can see the “you” entire, the way we do when we are leaving someone behind, “because we live by inches / and only sometimes see the full dimension.”

It may be too neat to say that this mirrors my own experience with Rich’s work—I can’t pretend to understand the full dimension of it—but these glimpses, these “inches,” of Rich that I received as a young woman undoubtedly steered my own identity and philosophy, as lover and writer of poetry, as a woman, as a person. To see the entirety is something else that art can teach us. It is not just a single poem or text that can resonate; watching the arc of a life unfold through a body of work can inspire. I can see Rich trying to answer the question of “Stepping Backward” about how to “have out our true identity” over the decades, refining her answer, finding more questions. This is solace, too: the art we love remains both static, in that it’s always available to us, and changeable—over the course of the artist’s life, and over the course of our own.

Colleen Abel is the author of two collections of poems, most recently Remake, forthcoming from Unicorn Press in 2016. Her poetry, essays, and reviews have appeared in Colorado Review, The Southern Review, New Orleans Review, Pleiades, The Collagist, and elsewhere. She lives in southern Wisconsin.