This is the sixteenth in Critical Mass's new Second Thoughts series, curated by Daniel Akst. More about this series, and how to submit, here.

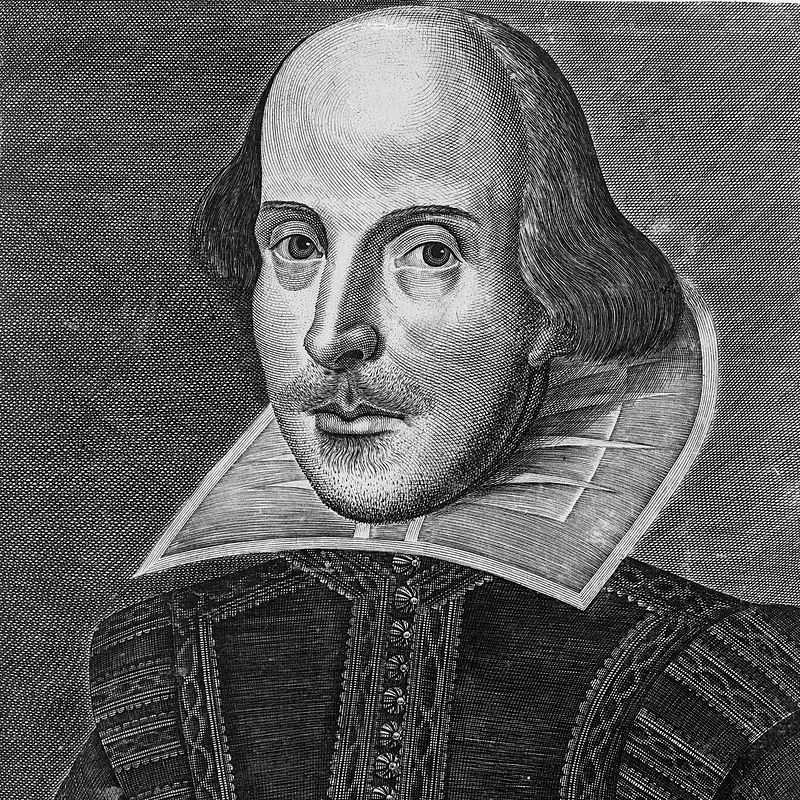

Securus judicat orbis terrarum, the Romans used to say – the whole world can’t be wrong. If there’s one thing that nearly the whole literary world has agreed on for 400 years, it’s the supreme greatness, the divine genius, of Shakespeare. “He was not of an age but for all time!” (Ben Jonson). “Others abide our question. Thou art free” (Matthew Arnold). “Shakespeare and Dante divide the world between them; there is no third” (T. S. Eliot). Even that intrepid icon-smasher Susan Sontag, when asked her favorite author, replied “Shakespeare.”

Securus judicat orbis terrarum, the Romans used to say – the whole world can’t be wrong. If there’s one thing that nearly the whole literary world has agreed on for 400 years, it’s the supreme greatness, the divine genius, of Shakespeare. “He was not of an age but for all time!” (Ben Jonson). “Others abide our question. Thou art free” (Matthew Arnold). “Shakespeare and Dante divide the world between them; there is no third” (T. S. Eliot). Even that intrepid icon-smasher Susan Sontag, when asked her favorite author, replied “Shakespeare.”

There is something empowering as well as constraining about a critical consensus. As a young reader adrift on the bounding literary main, I was glad to be sure of something. I read Shakespeare with reverence as well as gusto, conducting my quotidian internal dialogue in (very fractured) iambic pentameter for days after every exposure, happy to be intimate with – according to the highest authorities – “the best which has been thought and said in the world.”

Then Trickster – in the form of George Bernard Shaw – gave me a tumble. Shaw made his living for years as a drama critic, and in a tossed-off review of an apparently forgettable adaptation of The Pilgrim’s Progress, he observed in passing:

Search [in Shakespeare] for statesmanship, or even citizenship, or any sense of the commonwealth, material or spiritual, and you will not find the making of a decent vestryman or curate in the whole horde. As to faith, hope, courage, conviction, or any of the true heroic qualities, you find nothing but death made sensational, despair made stage-sublime, sex made romantic, and barrenness covered up by sentimentality and the mechanical lilt of blank verse.

Later, in the “Epistle Dedicatory” of Man and Superman, Shaw repeated this judgment, calling Shakespeare a mere “fashionable author who could see nothing in the world but personal aims and the tragedy of their disappointment or the comedy of their incongruity,” and who never understood that

true joy in life is being used for a purpose recognized by yourself as a mighty one; being thoroughly worn out before you are thrown on the scrap heap; being a force of Nature instead of a feverish selfish little clod of ailments and grievances complaining that the world will not devote itself to making you happy.

At first this didn’t compute. But on second and subsequent thoughts, it began to. Shaw frequently contrasted Shakespeare with Bunyan; that was my clue. By comparison with Bunyan’s, Shaw claimed, Shakespeare’s view of life was impoverished, his sense of motivation and personality cramped, his imagination fertile but only within narrow limits. His characters have no sense of a purpose larger than themselves, their political or romantic ambitions, their dynastic allegiances, and other trivial matters. Bunyan’s, by contrast, live by and for something truly great, a conception of stark moral and intellectual grandeur. Bunyan and his Hebrew forebears, if I understand Shaw correctly, were heroes because they cared little about their individual destiny, having identified themselves generously and wholeheartedly with an explicit cosmic moral order, unlike Shakespeare’s heroes, with their comparatively trivial purposes and preoccupations.

There was nothing vital at stake, at least as represented by Shakespeare, in the quarrels between English Catholics and Protestants: they were simply religious factional squabbles over political prizes rather than profound moral or metaphysical differences. The Hebrew prophets and the Puritans were — even if one rejects their beliefs and ideals — moral and religious geniuses and heroes. Shakespeare’s protagonists may have been brave or loyal or in other ways virtuous, but they are all the servants of paltry, utterly conventional purposes. Shakespeare was a fine dramatic craftsman and very clever wordsmith, but no more than that.

All this is what Shaw meant by saying that Shakespeare’s sense of life is hackneyed and petty, while Bunyan’s is vital and original. For all his profound psychological insight and dazzling verbal virtuosity, Shakespeare is the supreme exponent of the conventional moral and political wisdom. Of course, the conventional wisdom is still wisdom, even if not the highest. And wisdom is not, in any case, all literature has to give. But is Shakespeare the paragon, the nonpareil, I once assumed he was? I’m no longer sure.

Aesthetic judgments are hardly objective; often enough, they’re not even aesthetic. Taste, like morality, is an expression of temperament and circumstance. Perhaps I’ve grown querulous or snobbish, eager to épater my fellow critics. Perhaps I’ve grown doctrinaire, willing to subject authors to ideological interrogation. Most likely, I don’t understand – will never understand – the all-important distinction between form and content, which is why I value Tolstoy and Lawrence above Flaubert and Joyce, Bellow (or even Vidal) above Nabokov.

It’s probably too late for third thoughts, as I shift into a lean and slippered pantaloon. No matter: for better and worse, I’m no longer in quest of a philosophy of life. Whatever ultimate truths Shakespeare does or doesn’t have to offer, I look forward, before this strange, eventful history ends, to quaffing many a draft of his intoxicating word-music and lapsing contentedly into second childishness and mere oblivion.

George Scialabba is the author of What Are Intellectuals Good For?, The Modern Predicament, For the Republic, and the forthcoming Low Dishonest Decades (all published by Pressed Wafer). In 1991 he was awarded the Nona Balakian Citation for Excellence in Reviewing.