This is the ninth in Critical Mass's new Second Thoughts series, curated by Daniel Akst. More about this series, and how to submit, here.

The arrival of Spectre, the 24th official James Bond film from Eon Productions, in American theaters has been accompanied by the usual frenzy of 007 listicles, think pieces and arcana. The Bond films have demonstrated astonishing cultural longevity – it’s been 53 years since Sean Connery holstered his Walther PPK and launched a global phenomenon. But Ian Fleming and his superspy were already on the radar of the reading public a year earlier, courtesy of the kind of endorsement authors dream of.

The arrival of Spectre, the 24th official James Bond film from Eon Productions, in American theaters has been accompanied by the usual frenzy of 007 listicles, think pieces and arcana. The Bond films have demonstrated astonishing cultural longevity – it’s been 53 years since Sean Connery holstered his Walther PPK and launched a global phenomenon. But Ian Fleming and his superspy were already on the radar of the reading public a year earlier, courtesy of the kind of endorsement authors dream of.

In the March 17, 1961 issue of Life magazine, President John F. Kennedy provided a top 10 list of favorite books to journalist Hugh Sidey. Tucked in at number nine – beside appropriately presidential tomes such as The Red and the Black and Winston Churchill’s panegyrical biography of Marlborough – was Fleming’s fifth James Bond novel, From Russia With Love. By the year’s end, Fleming was the most popular thriller writer in America.

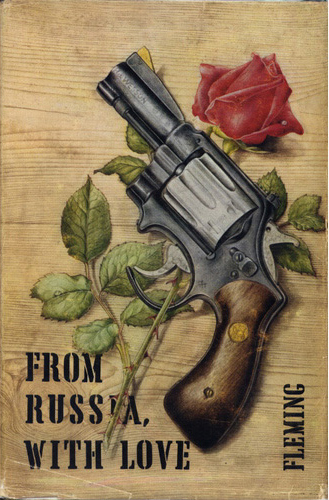

The Bond novels were staples of my youth, but I only recently returned to them on the occasion of Thomas & Mercer’s handsome reissues, which tempted me back to my favorite of the series. (The cover of the Jonathan Cape first edition of From Russia With Love remains the most prized of literary Bond collectibles.) In the intervening three decades, I’ve published and reviewed fiction, and taught novel-writing, and I came back to Fleming expecting the worst. Instead, I was surprised by how well the novel stood up, and how sound Fleming’s storytelling instincts are.

It would be easy enough to dismiss Kennedy’s move as the sort of political ploy we’ve come to expect from politicians who want to show us their human side, but it’s not hard to see why Kennedy might have been genuinely drawn to Fleming’s novel. First, though, let’s be clear: Fleming had no illusions about his literary gifts. “My books tremble on the brink of corn,” he once said. In a letter quoted in the recent collection, The Man with the Golden Typewriter, he insisted that, “My books are straight pillow fantasies of the bang-bang, kiss-kiss variety”

Still, one dismisses Fleming at one’s peril. Like other canny storytellers, he knows how to propel us through an utterly coherent universe. He has a knack for memorable villains, and From Russia with Love gives us not just one, but two of his greatest creations: the vicious assassin Red Grant and his creepy handler Rosa Klebb. Her description is particularly memorable:

The tricoteuses of the French Revolution must have had faces like [Klebb’s], decided Kronsteen, sitting back in his chair and tilting his head slightly to one side. The thinning orange hair scraped back to the tight, obscene bun; the shiny yellow-brown eyes that stared so coldly at General G. through the sharp-edged squares of glass, the wedge of thickly powdered, large-pored nose; the wet trap of a mouth, that went on opening and shutting as if it was operated by wires under the chin.

But disturbing super villains can be found throughout the Bond corpus. What Fleming does in From Russia with Love that differentiates it from the rest of series – and makes it the most compelling of his novels – is that he divides the story into two parts; and James Bond doesn’t even make an appearance in the first ten chapters. It’s a canny move, reminiscent of the way Fitzgerald holds Gatsby out of the first 50 pages of The Great Gatsby, which, I always point out to my students, allows tension and mystery to build up in the void. Though it’s no slight to 007 to say that he is barely missed in these fascinating pages.[1]

In “Part One – The Plan,” readers are treated to an extended look inside the Russian intelligence appartus, as a plan is hatched at the highest levels to wreak havoc and humiliation on the British by murdering 007 in a way calculated to maximize his disgrace. These sections, which consist largely of conference rooms and planning discussions, are riveting. Fleming had an intelligence background, and his knowledge seeps into all the Bond novels, but here, the authority and the detail are unmistakable. It’s easy to imagine the audience’s illicit thrill in 1957 upon reading this introductory note:

“Not that it matters, but a great deal of the background to this story is accurate. [… ] Today, the headquarters of SMERSH are where, in Chapter 4, I have placed them … The conference room is faithfully described and the intelligence chiefs who meet round the table are real officials who are frequently summoned to that room for purposes similar to those I have recounted.”

The ten opening chapters develop and tighten the conspiratorial noose, and although Fleming seems never to have met a backstory he could resist (the narrative momentum gets bogged down in occasional chapters of pure exposition), even the digressions feel lived in. They bear the pressure of the author’s experience and reek of gritty authenticity.

In “Part Two – The Execution,” the konspiratsia is put into motion though – as is usually the case with 007’s foes – it does not come off as its Russian spymasters intend. These chapters are full of the sort of memorable set pieces that one has come to expect from Fleming – the underground periscope which peeps into the Russian embassy, the fight at the gypsy encampment, the assassination of the killer Krilencu as he emerges through the mouth of a billboard Marilyn Monroe.[2] It’s no surprise that the novel was chosen for the second movie, and that the film version is among the most faithful to the novel.

We even get a too rare moment of emotion from James Bond, when he discovers the death of his Istanbul contact and friend, the irrepressible Darko Kerim, who has been murdered in his cabin on the Orient Express:

Half on top of him sprawled the heavy body of the M.G.B. man called Benz, locked there by Kerim’s left arm round his neck. Bond could see a corner of the Stalin moustache and the side of a blackened face. Kerim’s right arm lay across the man’s back, almost casually. The hand ended in a closed fist and the knob of a knife-hilt, and there was a wide stain on the coat under the hand.

Bond listened to his imagination. It was like watching a film. The sleeping Darko, the man slipping quietly through the door, the two steps forward and the swift stroke at the jugular. Then the last violent spasm of the dying man as he flung up an arm and clutched his murderer to him and plunged the knife down towards the fifth rib.

This wonderful man who had carried the sun with him. Now he was extinguished, totally dead.

Bond turned brusquely and walked out of sight of the man who had died for him.

He began, carefully, non-committally, to answer questions.

Fleming finishes the novel with all the flair you’d expect – a fight to the death with the murderous Grant aboard the Orient Express and a final showdown with Rosa Klebb in her suite at the Ritz hotel. He even manages a Reichenbach-esque ending (omitted from the film), in which Bond is nicked by Klebb’s poisoned shoe-blade and crashes to the ground on the novel’s last page. (Fleming had tired of his creation and decided to kill him off; fortunately, the conclusion is open-ended enough that it allowed Fleming, like Doyle, to change his mind and return Bond to active duty in the next novel, Dr. No.)

None of this is the stuff of high literature – Fleming’s love of coincidences, in particular, risks puncturing the narrative tension at several points; and the expository digressions later in the story can be rough sledding – but From Russia With Love offers a good deal more than “pillow fantasies,” and it’s marked by superior spy craft. John Le Carre may be a better storyteller; Raymond Chandler is surely a better stylist. But as a snapshot of the high end of Cold War genre writing, nobody does it better than Fleming.

Mark Sarvas’s second novel, Memento Park, is forthcoming from Farrar, Straus, Giroux.

[1] Fleming would try a variation on this device, to disastrous effect, in The Spy Who Loved Me, which is told in the first person point-of-view of the heroine Vivienne Michel. Bond only appears at the end, to save her from the bad guys. Fleming essentially disowned the novel, contractually committing the film producers to use no part of his story.

[2] In the film version, producer Albert Broccoli replaced Monroe with Anita Ekberg, the better to promote his own film, Call Me Bwana.