What are your favorite books about books? Why are these books such a ferocious pleasure? Maybe it's their range: books on books can combine memoir and criticism (see Rebecca Mead's 'My Life in Middlemarch' or Janet Malcolm's 'Reading Chekhov'), history and sociology (Alberto Manguel's 'A History of Reading'), humor, travelogue, astute observation, and who knows what else (Elif Batuman's 'The Possessed'). Tell us about your favorite for the latest installment of the NBCC Reads series, which draws upon the bookish passions of NBCC members and honorees and is curated by Alan Cheuse Emerging Critic Natalia Holtzman. (The series dates back to 2007; you can explore the archive here.) Submissions can be 500 words or fewer and should go to nbcccritics@gmail.com.

In early-2014, the bibliomemoir genre went through some sort of revival with three new books in quick succession: Rebecca Mead's 'My Life in Middlemarch'; Wendy Lesser's 'Why I Read: The Serious Pleasure of Books'; and Samantha Ellis' 'How to Be a Heroine: Or, What I've Learned From Reading Too Much'. Joyce Carol Oates had reviewed Mead’s book favorably at the New York Times and given a precise description of the bibliomemoir:

“Rarely attempted, and still more rarely successful, is the bibliomemoir — a subspecies of literature combining criticism and biography with the intimate, confessional tone of autobiography. The most engaging bibliomemoirs establish the writer’s voice in counterpoint to the subject, with something more than adulation or explication at stake.”

As if in counter, Christian Lorentzen had then satirically swatted at bibliomemoirs at the London Review of Books. In a fictional conversation with a literary agent, he lampooned bibliomemoirists who consider their voracious reading appetites to be sufficient qualifications for writing books about books.

Still, I remain a fan of the well-written bibliomemoir and, in early-2014, I wrote a six-part series exploring why/how they’re written, why we read them, the four specific types (along with micro-reviews of ~50 such books published from 1990-2014), and their literary value and relevance beyond giving us the bibliomemoirist’s anthropology of reading (cf. Tim Parks, New York Review of Books, 2014)

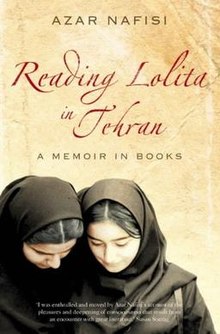

My all-time favorite bibliomemoir is the 2003 book, 'Reading Lolita in Tehran: A Memoir in Books' by Azar Nafisi. During the late 1990s, Nafisi, an Iranian university professor at the time, gathered a handful of former students in her home on a weekly basis to read Western literature, which was forbidden by law. As they read various classics — 'Pride and Prejudice,' 'Washington Square,' 'Daisy Miller,' 'Lolita' — they also share details about their difficult lives and the oppressive political regime. There are Nafisi's own memories of growing up in a conflict-ridden country and the history of the Iranian revolution and the Iran-Iraq war as seen through the eyes of women — all written in a clear, earnest voice that stays with us long after we've finished reading.

The most fascinating parts are the discussions between the women, both about the books and their lives, because their (hitherto mostly unvoiced) opinions grow bolder and more interesting as the narrative progresses. Whether they’re relating to the stories and characters or not, their unique and deeply personal interpretations, in the context of their own social histories and cultural traditions, are eye-opening for those of us not familiar with how totalitarian regimes, particularly Iran then, operate.

This book should be on every bibliophile’s and literary critic’s reading list because it shows us the power of stories to transcend cultural boundaries and to ignite minds. Beyond validating what should be the underlying thesis of every bibliomemoir — why and how a book is important or life-changing for the bibliomemoirist — Nafisi gives us fresh, new ways of considering these well-known Western classics too. If we read attentively enough, she repositions these classics entirely by upending much of what we’ve been told by scholarly defenders of the western literary canon. This book gives us a sum — of memoir, history, and literary criticism — that is considerably greater than its parts.

[Note: I recommend going in with some prior knowledge of all the referenced books, which are provided in a handy reference list at the end.]