This is the fourteenth in Critical Mass's new Second Thoughts series, curated by Daniel Akst. More about this series, and how to submit, here.

As is so often the case with such exercises, the premise of this one–literary second thoughts–mentally handcuffs me at first, for the question seems simultaneously too narrow and too broad. Like many working critics, I suspect, I have neither the time nor the inclination to revisit the judgments I scatter so carelessly in my wake, affecting instead a kind of jaunty nonchalance, a faux-working-journalist pride in the reviews’ essential ephemerality. This is a pose, of course: secretly I archive and catalogue my reviews painstakingly, even though I may publicly deem them good for wrapping fish and nothing else. The cataloguing does not, however, extend to actual reconsideration of their contents; I am either too self-confident or too fragile — I am not sure which — to spend much time worrying retroactively about the accuracy of my judgments.

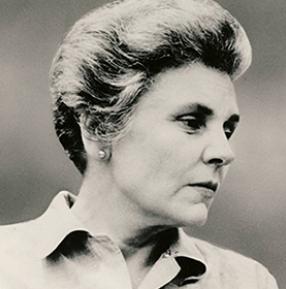

Of the writers who end up making a more lasting impact on me, the ones that I cherish and talk about with friends and think about late at night, conversely, the concept of “second thoughts” seems puny and inadequate: second and third and fifth and seventh thoughts, a lifetime of thoughts, a stream of reaction and consideration and shifting allegiance — something akin to what Harold Bloom terms agon — would be more accurate. The Portrait of a Lady does not mean to me now what it did when I was 22, nor, I expect, what it will, God willing, when I am 72. In the spirit of the question, though, I am willing to spend a few pleasurable moments, as I do with increasing frequency, thinking of Elizabeth Bishop.

It is difficult for me to recall exactly when I first encountered Bishop, largely because she initially made very little impression at all. I do remember “One Art” serving as the epigraph for Melissa Bank’s The Girls’ Guide to Hunting and Fishing, but that poem, as marvelous as it is, is both regrettably over-exposed and also, perhaps not coincidentally, almost singularly unrepresentative of Bishop’s oeuvre. In my twenties and thirties I was smitten with John Berryman and the Dream Songs, whose chaos and intensity were far more attractive to my sensibility than Bishop’s careful, somewhat pallid (so I thought) verse. Now that I’m 47, however, Berryman strikes me as shrill, histrionic, fundamentally adolescent: all that alcohol and lust and insanity just seems a bit… de trop.

Bishop’s poetry, in contrast, seems to deepen and broaden in my mind, with her conversational tone — so seemingly artless and off-the-cuff — and her cheerful, sturdy good sense increasingly in alignment with the contours of my inner emotional landscape. Berryman and his ilk make poetry seem hard and dangerous, which is actually rather easy, if you have the right temperament. Bishop makes poetry seem easy, which is in fact immeasurably harder; her best poems, beneath the silky hum of their cadences, are searching and tough-minded, and her words – “the gray sidewalk, the watered street”; “a weak-mailed fist clenched ignorant against the sky” — chime unbidden in my mind’s ear at unexpected times. There is a suppleness and an imaginative reach to her sensibility that unfurls itself relatively slowly; having second thoughts, and more, about such a writer is easy, and even inevitable.