“What's your favorite first book by an author ever?” That's the question that launches the seventh year of the NBCC Reads series, which draws upon the bookish passions of our members and honorees. Here's the eighth in this new series. It's not too late to send your critical essay on your own favorite to janeciab@gmail.com.

“What's your favorite first book by an author ever?” That's the question that launches the seventh year of the NBCC Reads series, which draws upon the bookish passions of our members and honorees. Here's the eighth in this new series. It's not too late to send your critical essay on your own favorite to janeciab@gmail.com.

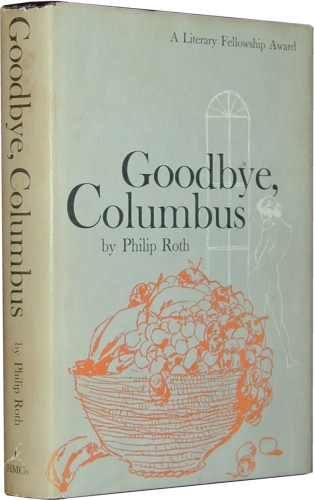

In Claudia Roth Pierpont’s Roth Unbound: A Writer and His Books, Roth acknowledges and explains some of the missteps in his early books—the presence of Jews in Goodbye Columbus’s Short Hills, NJ, the excessive length of Letting Go, the flawed final chapter of Portnoy’s Complaint—but unlike some authors, he doesn’t disown the first one. And why should he? Fifty-five years after publication, it remains a vital collection of short fiction.

Lots of my favorite first books tend to be collections. The stories in Raymond Carver’s Will You Please Be Quiet, Please? are unforgettable because of their protagonists’ inability to hold back what shouldn’t be said. This problem could be said to inflict the characters in Mary Gaitskill’s nitro-packed Bad Behavior and Sam Lipsyte’s Venus Drive. Then there are the short, energetic first novels by Jay McInerney, Donald Antrim, and Nicholson Baker. Bright Lights Big City, Please Elect Mr. Robinson for a Better World, The Mezzanine…all of these are favorites, too. And finally, the barely sane outpouring of Frederick Exley’s A Fan’s Notes, the wild ambition of Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man, and the deadpan assuredness of Thomas Pynchon’s V., each of which disprove the notion that a writer’s ambitious first novel will tend to be more flawed than brilliantly imperfect (David Foster Wallace’s The Broom of the System and Don DeLillo’s Americana, on the other hand, suffer from this syndrome).

Goodbye Columbus is not quite my favorite Roth—The Counterlife and The Ghost Writer are far more wild and masterful—but the collection’s eponymous novella crackles with a youthful enthusiasm for life and literature (“I read Mary McCarthy,” the protagonist declares to his partially attainable sweetheart) that instantly drew me into its world and called on a string of bittersweet fictional summers, from The Great Gatsby to last year’s A Map of Tulsa by Benjamin Lytal.

Neil Krugman, a 23-year-old philosophy major, spends half his week employed at the Newark public library and the rest crashing the pool at the country club. Soon after a pretty girl asks him to hold her glasses, the two are playing at being in love, even after she presses the hard questions about what he's doing with his life. “I'm not a planner,” he says to her, but it's not the whole truth.

Neil is ambivalent with Brenda, repulsed by the privilege and self-denial of her nose job even as he is allured by its effect. The revelation that Brenda goes to college not only in Boston but at Radcliffe crystalizes the class-consciousness that had already stirred in him by the contrast of cool summer nights in Short Hills with his own family's heritage of dense, sweltering Newark. He wants to escape, but it's not just the fate of his family that he's fleeing. He's trying to break loose from fate itself, and what better way than to spend week-long sleepovers with his new girlfriend and her gluttonous family in their huge house? But the illusion is broken by the news that Brenda's older brother is engaged to be married. The fiancee's arrival “dramatize[s] the passing of time,” and reminds Neil that young people can and do get married. Two pages later he speaks out, refusing to keep quiet on something that Brenda does not want to hear about. “I want you to buy a diaphragm,” he says, “for…for the sake of pleasure.” “Pleasure?” she responds. “Whose? The doctor's?” “Mine,” he replies flatly, and here we have the first emergence of a voice that is uncompromising and undeniably Rothian. “That's right. My pleasure. Why not!” That exclamation point!

When the conflict is re-ignited at the end of the novella, with Brenda back at school and Neil visiting on a holiday weekend, he is even more forceful, and says things that leave him no way to turn back. Does he do it because he fears rejection and figures it best to strike preemptively, or is he simply ready to move on? He doesn't seem to know for sure, but the uncertainty sets him up for a beautiful final scene, where his ugly anger and bitterness dissolve into earnest contemplation. While sulking through Harvard Yard in the middle of the night, on the verge of throwing a rock through the front of the Lamont Library, he catches his reflection in the glass and wonders, “What was it inside me that had turned pursuit and clutching into love, and then turned it inside out again?…I looked hard at the image of me, at that darkening of the glass, and then my gaze pushed through it, over the cool floor, to a broken wall of books, imperfectly shelved.”

The five stories that follow, most specifically “The Conversion of the Jews,” “Epstein,” and “Eli, the Fanatic,” scratch furiously at the cracks in an imperfect facade. A Jewish boy named named Ozzie, who won’t shut up about Jesus Christ, forces his rabbi to declare belief in immaculate conception; a philandering family man is caught with syphilis; and a suburban lawyer, charged by his community with shutting down an illegal yeshiva, boldly wears the “strange” black clothes that belonged to the same Hasidic man whose presence in town had ignited the fervor. Despite being told in the third person, these three stories feature powerful voices, characters who threaten to push through the walls that are meant to contain them. In this regard, they anticipate many of Roth’s first-person protagonists. If developed into novels, they might even hold their own among the best (and worst) of them.