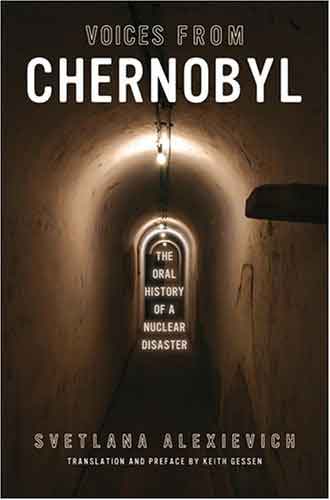

For the latest iteration of NBCC Reads, we've asked members and friends of the NBCC to share their favorite works of literary journalism. Below, member Richard Z. Santos discusses Svetlana Alexievich's Voices From Chernobyl: The Oral History of a Nuclear Disaster.

For the latest iteration of NBCC Reads, we've asked members and friends of the NBCC to share their favorite works of literary journalism. Below, member Richard Z. Santos discusses Svetlana Alexievich's Voices From Chernobyl: The Oral History of a Nuclear Disaster.

Anyone who’s read even a page of Voices from Chernobyl: The Oral History of a Nuclear Disaster (2005 Winner of the NBCC award for Nonfiction) understands why this marvelous, unusual book has been stuck in my head for years. Journalist Svetlana Alexievich spent a decade interviewing survivors of the worst nuclear accident in history. Voices presents their testimony without any editorial guidance or authorial intrusions—there’s only a brief prologue by the translator and a few pages labeled “In Place of an Epilogue” by Alexievich.

Alexievich groups the testimonies under loose thematic headings: “Monologue About Lies and Truth,” “A Scream,” “Three Monologues about a Single Bullet.” These stories range in length from a single page to ten-plus pages. Each person tells a story of almost unbearable human endurance and tragedy. It’s a book I could only read a page at a time, scattered over months.

“Even if it’s poisoned with radiation, it’s still my home. There’s no place else they need us. Even a bird loves its nest…”

To me, the most powerful sections are the choruses, including: “Children’s Chorus,” “People’s Chorus,” “Worker’s Chorus.” Just a few sentences each, separated by bullet points, the choruses amplify the tragic absurdity of the corruption and lax standards that precipitated the disaster and hindered the recovery.

The lack of an editorial apparatus brings an immediacy and tragic humanness to the voices: “I’m not a writer. I won’t be able to describe it. My mind is not enough to understand it….There you are: a normal person. A little person. You’re just like everyone else—you go to work, you return from work….You’re a normal person! And then one day you’re turned into a Chernobyl person, an animal that everyone’s interested in, and that no one knows anything about.”

Alexievich preserves her book’s power by reducing her own role. A different author might have had the urge to tell us what’s important, to tell us what’s tragic. But Alexievich allows the people to speak for themselves:

“I’m twelve years old and I’m an invalid. The mailman brings two pension checks to our house—for me and my granddad. When the girls in my class found out that I had cancer of the blood, they were afraid to sit next to me. They didn’t want to touch me. The doctors said that I got sick because my father worked at Chernobyl. And after that I was born. I love my father.”

Richard Z. Santos is a brand new NBCC member whose fiction and reviews have appeared, or is forthcoming, in Criminal Element, The Los Angeles Review of Books, Nimrod, Kill Author and Bartelby Snopes.