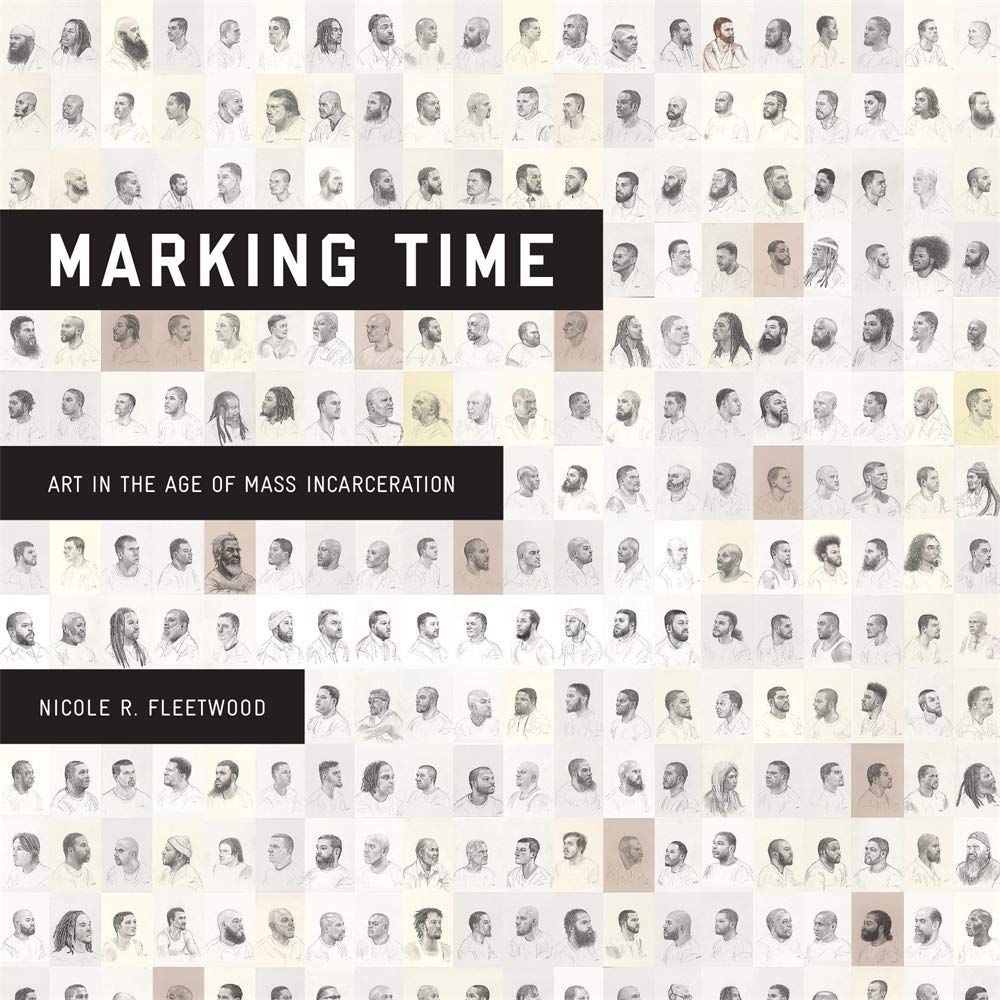

Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration by Nicole R. Fleetwood (Harvard University Press)

That few people believe prisons and museums have much in common is the literal and figurative quarrel that Nicole R. Fleetwood’s Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration takes up. In fact, both were instituted as diametric systems of governance via the Enlightenment. On one end, the museum as a shrine to pervading cultural ideas and practices; and, on the other, the penitentiary as an ordered and humane form of punishment. As time built the respective ivory and barbed-wire towers higher, the question of who deserves to be in either category quieted. “Fine artists” should be lauded, the imprisoned must be made right through punitive treatment, and we all lived happily ever after.

Documenting the thoughtlessness of this paradigm is notable enough, but Fleetwood’s project is significantly more ambitious. Profoundly revisionist, the book identifies the conditions under which incarcerated persons create art and taxonomizes its making. To be an artist in prison is to be confined by Penal Space: the prison environment, with all the “geographic, material, social, and psychic” implications of being under constant watch. Artworks made in the monotony of extended sentences (and outside of prisons through the strictures of parole) are impositions of Penal Time. Restrictions on what the imprisoned are allowed to possess as makers—as well as the body itself, as incarcerated persons forfeit their rights while in custody—count as Penal Matter. The liminal space between being sentient and being “reformed” by the penal system is designated a state of unfreedom.

It isn’t difficult to see how this reshuffles contemporary debates on both art history and institutional reform. One wonders how so-called Outsider Art would have been received by curators and critics if they had access to Fleetwood’s concepts. Prisons aren’t the only places where people are institutionalized, and the brilliance and durability of Carceral Aesthetics as a theory lies in the fact that it could be taken and applied to any situation where art-makers are being held by the state against their will.

But since Marking Time is concerned with prisons, it should be noted that it is one of the most damning critiques of prisons in recent memory. Its case studies perform double duty as a testament to human flourishing and an argument for the failure of the penal system on its own terms. Because if incarcerated persons (many of whom maintain their innocence) are dodging and defying prison regulations to acquire materials to make art; if cozy relationships with guards, including art exchanging hands, can loosen these restrictions; if people deemed the worst of the worst possess the same aesthetic capabilities as a gallery artist in spite of all that is imposed on them, how can mass incarceration (and, to some extent, the museum) be considered a success? It’s proof of Fleetwood’s acuity that, in a work that paves so much new road conceptually, she never loses sight of visibility and humanization as her goals.