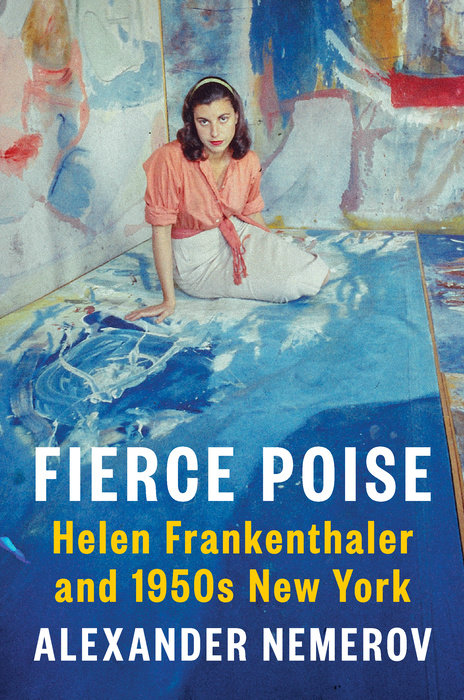

Fierce Poise: Helen Frankenthaler and 1950s New York by Alexander Nemerov (Penguin Press)

A few months into my five years of teaching philosophy at Bennington College, a faculty colleague, during a chat about how we could raise money for an on-campus project, cheerily suggested, “Well, we could always try to hit up Helen Frankenthaler.”

I knew her name but little about her work—call me a philistine—but with that proposal I immediately associated her with money. My colleague explained the full story and, with many painting students in my aesthetics classes, I soon learned as much as I could about one of Bennington’s most successful alumnae.

Not nearly as much, though, as I learned from Alexander Nemerov’s sharp, focused, critically enlightening Fierce Poise, which pulls off an admirable twin achievement. While describing, almost cinematically, how the distinguished mid-20th-century abstract impressionist aggressively rose to fame, he also—understandably for Stanford’s Chair of Art and Art History—offers many elegant, insightful assessments of her work, helping us to understand where she fits in the art of her time.

Nemerov faced a delicate task in taking on Frankenthaler. Son of the poet Howard Nemerov, himself a Bennington faculty member who taught Frankenthaler, the younger Nemerov grew up in Bennington conscious of the artist, though he never met her. Yet his familiarity with her forces him to balance two aspects of her career that create tension: his admiration for her work, and his recognition that some art-world peers viewed her as an aggressively ambitious networker lacking any intellectual gravitas.

As he embarked on his own scholarly career in art, Nemerov confesses thinking she “epitomized the elitist and seemingly apolitical hauteur that my peers and I found troubling.” But he later revised that opinion, learning from Frankenthaler’s famously upbeat, romantic, brightly colored work “that joy was itself serious, that prettiness had its edges, and that guilt, anger, and indignation were not the only games in town.”

Nemerov makes clear on his first page that Frankenthaler’s tale is not the standard starving-artist plot: “She had money, she had means, and she knew how to get ahead.” Frankenthaler started at the top.

The daughter of a wealthy New York State Supreme Court judge and his highly cultured wife, both German-Jewish in their origins, Frankenthaler grew up in the world of Park and Fifth Avenues and the Metropolitan Museum. She attended elite private schools–Horace Mann, Brearley, Dalton– then moved on to Bennington, always a hotbed of experimental artistic intensity. Inspired by, among others, resident philosopher Erich Fromm, who advocated embracing freedom rather than escaping from it, she doubled down on her dream of becoming a famous painter.

Less than a year after graduation in 1949, she boldly phoned New York’s most influential art critic, Clement Greenberg, nearly twenty years her senior, and invited him to a gallery show of works by recent Bennington grads. She then began a five-year relationship with him that drew her into the big leagues of Manhattan’s art and intellectual worlds.

Frankenthaler found herself mixing with Jackson Pollack, Willem de Kooning and other major painters of the time. William Phillips, Partisan Review’s editor, liked her “sharp and cynical but good-natured wit, slightly Jewish in its irony and irreverence.” But not everyone in her elite new world was so charmed.

Nemerov notes that her relationship with Greenberg “struck observers as a power grab on her part.” Three years after leaving Greenberg, she married the distinguished and very wealthy painter Robert Motherwell—many peers, Nemerov remarks, saw it another “strategic alliance.” A reputation for partnering with powerful men—after divorcing Motherwell, Frankenthaler conducted an affair with Andrew Heiskell, CEO of Time Inc.—clung to her among some art-world observers. Nemerov comments that she was “intent on getting her way…promoting herself—she did not mind how she came across. Naturally, she rubbed people the wrong way.” Barnett Newman thought her “cunning” and a publicity hound.

At the same time, Nemerov generously makes an effort to explain Frankenthaler’s driven personality, locating its cause in a “deeply neurotic” Jewish anxiety that often left her with dread that she’d die young, before making her mark. He details how her relationship with Greenberg disintegrated in part because of the clash between the critic’s self-defined “Jewish self-hatred,” a rage rooted in his lower-class Polish-Jewish Bronx upbringing, which grated against her decorous, upper-class German-Jewish sophistication, itself a mask for high-functioning depression.

Nemerov remains a champion of Frankenthaler’s art throughout Fierce Poise. Putting aside the painter’s later evaluation of herself as “square and bourgeois,” and regretting her attack on younger artists such as Mapplethorpe and Serrano as “mediocre,” Nemerov finds that she painted with a “brazen but gentle freedom,” a “sense of art as a spilling out.” Nemerov sees “a specifically inward feeling to this freedom, a recognizably Jewish one as well,” and emphasizes “the Jewishness of Helen’s art itself.”

One of Frankenthaler’s foundational aesthetic beliefs was that “No painting is good `intellectually.’” Rather, contends the author, “she pursued an art of immediate impressions,” a way, her nephew told Nemerov, “to get up and out from the family darkness.” (Her mother committed suicide in 1954 by jumping from her 14th-floor apartment at 5th Avenue and 74th Street).

“I think of my pictures as explosive landscapes,” Frankenthaler explained, “worlds and distances held on a flat surface.” Nemerov agrees: the abundant color in Frankenthaler’s work “is loud, it insists, even over-insists in the manner of a young person having her way, that there is no night, no darkness, no death, that can hide this brightness the artist equates with life itself.”

Carlin Romano teaches media theory and philosophy at the University of Pennsylvania and is the author of America the Philosophical (Alfred A. Knopf/Vintage).