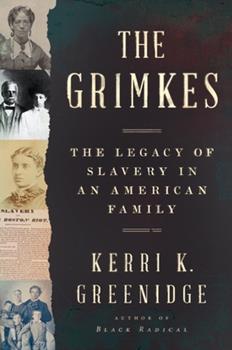

Sarah and Angelina Grimke have been celebrated as the sisters who came to abhor the slave system upon which their prominent South Carolina slaveholding family’s wealth depended. They defied the family values of Episcopalian piety and antebellum Southern culture, and moved north, to Philadelphia and Boston, and embraced William Lloyd Garrison’s radical call for the abolition of slavery as well as the idea of liberating women.

The Grimke sisters may have been exalted in the public imagination as brave abolitionists and advocates for suffrage, but in her revelatory investigation, Tufts University historian Greenidge challenges these myths. In the story of the two sisters, she uncovers a gnarled family tree, rooted in moral contradiction and generations of trauma.

As the sisters agitated for change, they benefited financially from their slaveholding family. Greenidge dug deeply into this family history and traces how this contradiction played out through generations. The Grimkes (Liveright), she writes, “is thus a family biography that resonates in the lives of those who struggle with the personal and political consequences of raising children and families in the aftermath of twenty-first-century betrayal of the radical human rights promise of the 1960s.”

Like Annette Gordon-Reed’s Pulitzer-winning The Hemingses of Monticello, Greenidge illuminates the dynamic of racial subordination within a slaveholding family and how a free white man who conceives children with enslaved Black women, whether from a relationship spanning decades or from a rape, destroys a family for generations.

Only after the Civil War did Angelina find a reference in the National Anti-Slavery Standard to a Black student named Grimke who had delivered a stirring address at Lincoln University. The sisters learned that their violent brute of a brother had fathered sons with a woman he had enslaved and that this student was their nephew. They provided financial assistance so that nephew Francis “Frank” Grimke could attend Princeton Theological Seminary and his brother Archibald (“Archie”) could proceed to Harvard Law School.

The nephews achieved phenomenal success, and their often-condescending aunts never let them forget that they had helped. Both part of the “colored elite,” Frank presided over the Fifteenth Street Presbyterian Church in Washington, D.C., and became one of the nation’s leading Black ministers, and Archie co-founded the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. The brothers were dedicated to self-improvement and racial uplift, not rebellion, and, as Greenidge deftly explains, they distanced themselves from slavery and believed they belonged to a “select class” distinct from the “negro masses.”

Greenidge—whose earlier book, Black Radical, was an excellent biography of activist newspaper editor William Monroe Trotter and won the Mark Lynton History Prize—makes a brilliant choice to end her extraordinary family biography with Angelina Weld Grimke, the daughter of Archie and his wife, Sarah Stanley, the white daughter of a Midwestern Episcopal clergyman who had opposed the marriage.

This Angelina (nicknamed “Nana”) was a creative and independent spirit, a poet and playwright who loved who she loved—a man, then mostly women—and rejected domesticity. Yet she was plagued by her family’s past. “Nana embodied all of the contradictions of the era’s politically neutered yet culturally pretentious colored elite,” Greenidge writes, and she was “so heavily policed by the culture of racial respectability that she would never use her relative privilege to meaningfully uplift the ‘negro masses’ from whom she remained so personally estranged.”