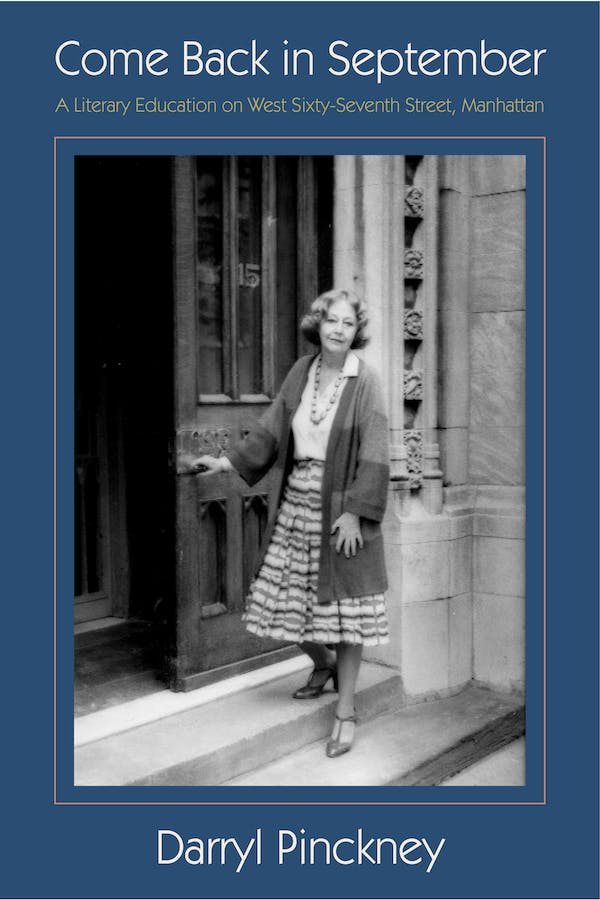

Consummate essayist and novelist Darryl Pinckney’s lively and layered memoir has so much going on—any given page is rich with anecdotes, insights, and searching questions—that it eludes a quick summary.

Where to start? Well, Come Back in September (Farrar, Straus and Giroux) is about Pinckney’s longtime friendship with Elizabeth Hardwick, which began during his student years at Columbia in the early 1970s, when he took a poetry class across the street with her at Barnard. It’s also about Hardwick, her life and work and stewardship of Robert Lowell’s work after his death; and about their milieu of critics, poets, and novelists. Mary McCarthy and Susan Sontag make regular visits at Hardwick’s apartment, where a young Pinckney joins in the conversation. The book also makes room for a story of the New York Review of Books’ founding 10 years earlier, and of Pinckney time there in the mailroom, observing volatile co-founder Robert Silvers (he sees more of Silvers’s fellow editor Barbara Epstein at Hardwick’s place, as they’re neighbors and close friends). Eventually, Pinckney writes for the paper, laboring like Hardwick over a series of drafts. Ultimately, Come Back in September is about a Black gay man finding his place in the literary world while keeping up an active social life around campus and downtown, his young friends including the likes of Lucy Sante and Jim Jarmusch.

To be sure, there’s no shortage of privileged gossip. Several lines from Hardwick are followed by her ordering him not to repeat what she tells him (Philip Roth’s The Ghost Writer is a “joke,” in her view). But this is not one of those stories of lucking into the right place at the right time and getting a leg up from the right people. It’s a story about hard work and learning from others, the greatest lesson being that writing doesn’t get easier, something Pinckney conveys in careful depictions of Hardwick’s and Sontag’s moments of vulnerability and self-doubt. Along the way, Pinckney toils and sweats through various entry-level publishing gigs, his experience familiar to anyone who’s started out in the Manhattan meat grinder. This passage is particularly acute:

“It was impossible to feel clean. The lunch-hour rivulet of sweat down my spine instantly chilled in the air-con of the office lobby. Phoning, making appointments, listening to excuses, hassling over contracts…. I seldom went into Central Park and whenever I did, I risked getting turned around. I went down paths at top speed, as if on the lam, worried about the office, my desk at home, people I might have disappointed or offended, everything I’d not done, not read, not experienced, never would.”

The stories and literary insights alone are worth the price of admission, but what makes this book so remarkable is the immediate sense of a young writer’s life and the world around him, which Pinckney’s recreated by drawing from his extensive diaries. The book ought to be an inspiration: take the time to write everything down.